Who decides how much water we use to live, sow, or produce? In Peru, that task is in the hands of the National Water Authority (ANA), the state body that regulates the use of the country's most vital resource.

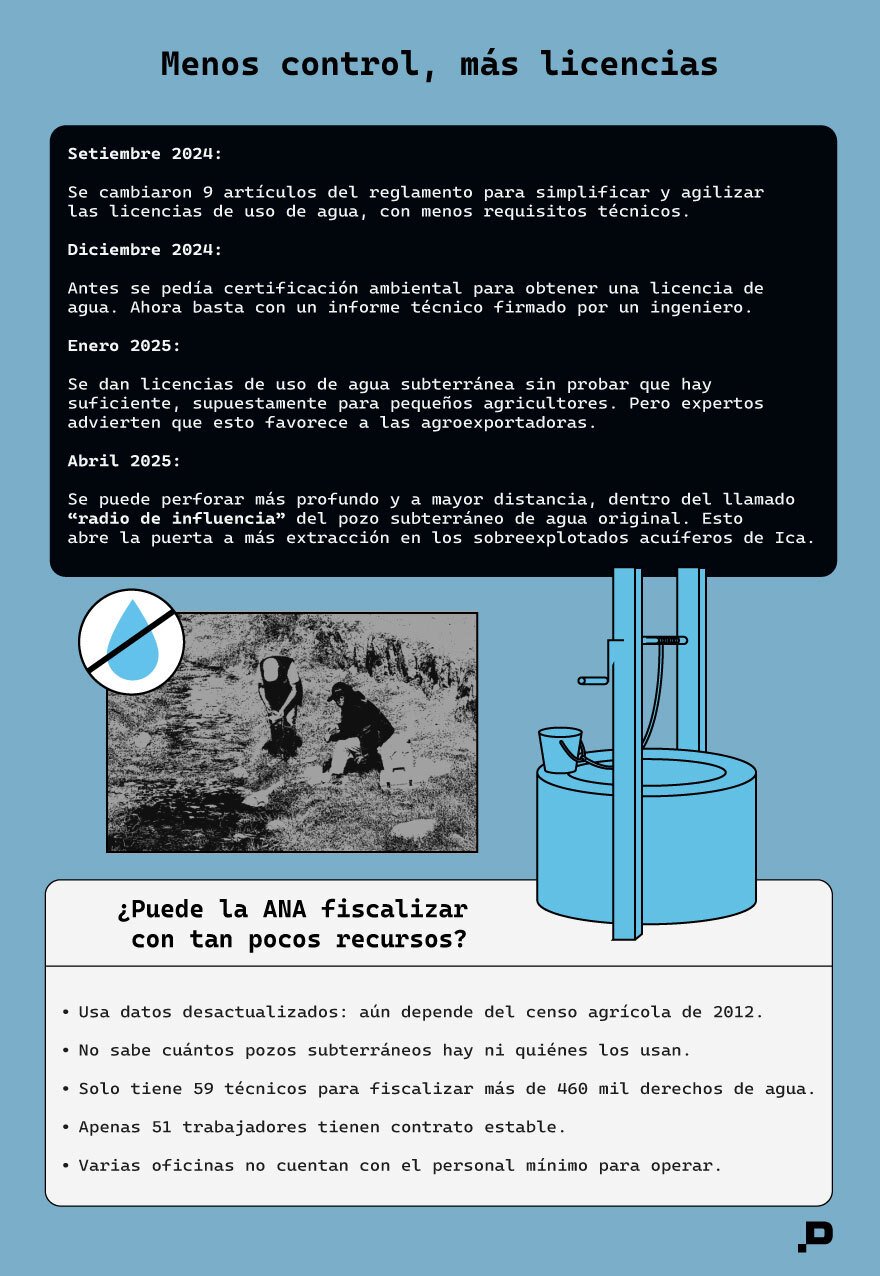

The Water Resources Law mandates the ANA to care for and manage rivers, lakes, and aquifers (underground water reserves). It also grants it the power to issue licenses for different uses—such as consumption by the population, agriculture, industry, or mining—and to inspect wells to control how much water each sector extracts. In September 2024, the government announced a profound restructuring of this entity, which depends on the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Irrigation (Midagri). It was presented as a response to corruption and poor management.

However, this investigation by Salud con lupa reveals that the ongoing reform weakens the ANA's supervisory capacity and aligns its operation more closely with the interests of those who consume the most water: agro-export and agro-industrial companies. Leading this process is the Minister of Agrarian Development and Irrigation, Ángel Manero Campos. His family is linked to Sunshine Export, a mango and avocado exporter where his wife, Silvia Wong Wu, is a shareholder and works as the commercial manager. The company is part of the Association of Peruvian Agricultural Producers Guilds (AGAP), the sector's most influential business group.

Since taking office in April 2024, Manero has publicly defended the need to "return the promotional framework that the agro-export sector enjoyed before the repeal of the original Agrarian Law." However, so far, he has not commented on his possible conflict of interest or provided explanations about the scope of the ANA reform, which is advancing without major public debate and with direct impacts on water regulation.

To head this process, Minister Manero appointed his advisor Álvaro Quiñe Napuri as president of the reorganizing commission. An agricultural engineer, Quiñe had previously worked in at least five agro-industrial companies—including Agropecuaria San Eugenio, Agrícola Chapi, and Natufrut Trading—in positions related to commercial and operational management.

His background is not free of controversy. In 2017, he was disqualified from civil service for five years after presenting a false professional degree to assume a position in Agro Rural. He claims he was the victim of a maneuver. "They planted a photocopy of a false degree in my file," he stated in an interview with Salud con lupa. Despite this background, in April 2024, he was incorporated into the ministerial office as a high-level advisor, and a few months later, he was tasked with leading one of the sector's most sensitive reforms.

According to an official diagnosis prepared by the ANA itself, the entity has been dragging serious deficiencies since its creation in 2008: institutional disorder, low management capacity, and difficulties in fulfilling its functions. This is especially concerning considering that nearly 80% of the country's available water is allocated to agriculture, and most usage rights are concentrated in the hands of about 50 large companies.

A review of official water usage records for agricultural purposes allowed us to identify that ten companies and three individuals concentrate more than 100 rights each. Topping the ranking are Agroindustrias San Jacinto and Casa Grande, both sugar companies of the Grupo Gloria dedicated to the cultivation, processing, and industrialization of sugarcane and its derivatives—such as sugar, alcohol, and bagasse. San Jacinto registers 420 water use rights and Casa Grande, 374. In third place is Complejo Agroindustrial Beta, with 256 rights, specialized in the production and export of asparagus, avocado, tangelo, and mandarin orange.

It is followed by Agroindustrial Laredo, with 237 rights, dedicated to the cultivation of sugarcane and the manufacture of sugar, molasses, and other derivatives. Other large agro-industries with high levels of water concentration also appear: Agro Industrial Paramonga, with 211 rights, focused on the production of refined sugar, alcohol, and thermal energy from cane; Sociedad Agrícola Rapel, with 201, one of the country's main table grape exporters; Agroindustrial Cayaltí, with 190, dedicated to the cultivation of sugarcane, cotton, tobacco, and hard yellow corn; and Agroindustrial RPC, with 142 rights, focused on providing services, technology, and supplies to the agricultural sector. Agrícola del Chira and El Pedregal complete the list, with 139 and 117 rights respectively, both oriented towards export fruit crops.

In addition to the companies, four individuals also stand out among the largest holders of water use rights: Marco Antonio Rabanal Díaz, with 111 rights; Darío Magno Alvites Diestra and Nancy Vicenta Laynes Odiaga, with 101 combined.

Despite this reality, the ANA does not have updated basic information. In most of its regional offices, there are no current inventories of surface water sources (such as rivers and lagoons) or aquifers. The records of drilled wells and existing hydraulic infrastructure, such as canals, intakes, or reservoirs, are also not updated. This lack of data seriously limits its capacity to plan, allocate, and supervise water use in the country.

The diagnosis also warns that both formal and informal users intervene in the scheduling of water distribution in the valleys, that is, in how it is allocated between zones and crops. By modifying these rules, conflicts are generated with user boards and with special projects that depend on technical and orderly management of the resource.

Furthermore, many companies and individuals drill wells without authorization and extract more groundwater than permitted. This overexploitation not only reduces the available quantity in the aquifers but can also affect their quality. Those who operate informally also do not pay the fees intended for monitoring and managing groundwater, nor the economic retribution that corresponds to the State for the use of the resource.

Under these conditions, between September and November 2024, Álvaro Quiñe was in charge of the reorganization of the National Water Authority. At the end of his assignment, he presented a 173-page report, which we accessed through a public information request. The document reveals that, under the argument of simplifying procedures, it has been proposed to reduce controls and grant greater flexibility to issue water use licenses, even in areas where the resource is already in a critical situation.

The Reorganizing Commission's report argues that one of the main obstacles to formalizing water use in agriculture is the obligation to present an approved environmental study, as required by the National Environmental Impact Assessment System. It indicates that this requirement, necessary for any productive activity, can be costly and take a long time, which discourages water users—especially small farmers—from starting the formalization process.

Quiñe defends the approach adopted. “The reform favors everyone: small, medium, large. The small farmer suffers more to formalize irrigation than the large exporter, since the processes are cumbersome, inefficient, and very costly. The idea is to democratize water licenses. As it is, both the large and the small suffer,” he assured in an interview for this investigation. But the facts do not fully support that argument. Some of the proposals included in the report have already become current regulations, although they have gone unnoticed.

One of the measures approved in January 2025 was to eliminate the requirement to present a technical study to verify if water is available before granting groundwater use licenses. Since then, farmers with plots of up to 10 hectares can obtain a license without needing to demonstrate that the aquifer has the capacity for new extractions.

The change was presented as relief for family agriculture, but experts and rural leaders warn that it is far from addressing their reality. Capturing groundwater is not simple: it involves drilling wells, buying equipment, and investing in pumping and irrigation systems, all with high operating costs and energy consumption. For most small farmers, these investments are unattainable. In contrast, those who can bear that expense—the agro-exporters—end up being the main beneficiaries of this flexibility.

In regions like Ica, drilling a well can cost more than 100 thousand soles (approx. $26,000 USD). Miriam Bautista, a farmer in the Casablanca sector, explains that, in her case, opening a well for her three-hectare plot would cost around 50 thousand soles. “First you have to dig the hole, then install the geomembrane [a thick plastic], and then the entire drip irrigation system. It's an enormous task,” she asserts.

Juan Alberto Mere García, president of the Board of Users of the Minor Hydraulic Sector Ica, says that among the eight thousand farmers associated with his organization, none have more than four hectares, and drilling a well is beyond their means. “Even if you have ten hectares, how much does it cost to drill the well? It is very complicated. I don't think it would be possible,” he states.

This gap between the approved regulation and reality is also noted by Pavel Aquino, an expert in water resources and former environmental evaluation coordinator at the ANA. According to him, family farmers rarely access wells, either on the coast or in the highlands and jungle. Instead, coastal agro-exporters—especially in regions like Ica and Tacna—are the main users of aquifers, precisely where state control is weakest.

Aquino warns that the new regulation would not only fail to benefit small farmers but could even give a legal appearance to informal wells already operated by large companies. At the time, a report by the ANA itself—presented in 2012—already showed the magnitude of the problem: in the Ica aquifer there were 864 groundwater wells, but only 249 had a license. In Villacurí, out of 460 wells, 321 were informal; and in Lanchas, 373 out of 436 did not have authorization. Since then, the situation has evolved.

According to a more recent report—sent by the Board of Users of Underground Water of the Ica Valley (JUASVI) to the ANA in August 2023—there are currently 2,365 wells in the Ica valley, of which 1,350 are operational.

“Ten hectares is too much for what we understand as family agriculture. On average, plots do not exceed five hectares, and that happens when several families associate. This regulation can be used by agro-exporters or informal actors to present themselves as small farmers and thus legalize their operations,” says Aquino.

Environmental lawyer Rasul Camborda adds another alert. He recalls that previous formalization processes for small users never required environmental studies. “In a 2014 regime, they basically asked you to demonstrate that you had been using the water between two and five years before, and then you moved to the formalization process,” he explains. And he raises a key question: “Who were really asked for an environmental study? Because behind it, perhaps, is not the farmer with his small plot, but much larger actors.”

According to Camborda, if the current regulation also exempts those who concentrate large volumes of water from presenting environmental studies, we would be facing a regulation tailored to their needs. “Due to the amount of water they use, they should go through an environmental evaluation,” he warns.

The concerns are not isolated. Organizations such as the Peruvian Society of Environmental Law and the NGO Law, Environment, and Natural Resources have warned that measures such as automatic licenses prioritize the interests of large users and weaken control mechanisms, just when the country faces an increasingly acute climate crisis.

More Pressure Where Water Is Already Scarce

As part of the same reform process, on April 21, 2025, the National Water Authority modified the rules for groundwater use in Ica again. This time, it further relaxed the ban that protected the aquifers of Ica, Villacurí, and Lanchas, three areas where the resource is already severely overexploited.

This change breaks with what had been decided in 2009, when it was indefinitely prohibited to grant new licenses to drill wells or carry out hydraulic works in these areas. In 2011, an exception had already been made: the so-called "replacement wells" were allowed, but with very clear conditions. The new well had to have the same flow rate, meet strict technical requirements, and be no more than 100 meters from the previous well. Now, those conditions have been relaxed. It is allowed to drill a deeper well if the previous one has lost capacity, and it is no longer necessary for it to be close: it is enough that it is within the so-called "radius of influence" of the original well, a much broader area with no clear limits.

For Pavel Aquino, a water resources specialist and former ANA official, this regulation makes it easier for large agro-exporters to replace their depleted wells without major restrictions. “The regulation enables operational continuity with technical support, which is usually applicable to agro-export companies with current rights,” he explains. In contrast, small farmers can hardly comply with the technical and economic requirements demanded by this new process.

Aquino also warns that changing the location criterion—from a fixed distance to the “radius of influence”—can have unintended effects. “In practice, a new radius of influence is being generated that affects other areas that were previously protected,” he points out.

The current agricultural model, based on export monocultures such as asparagus, avocados, blueberries, and grapes, demands large volumes of irrigation water. Meanwhile, many rural and high-Andean communities see aquifer levels drop, their lagoons and rivers dry up, and they are not guaranteed access to water for their crops, their livestock, or even for basic household use. This is warned by the recent report How fair is our water footprint in Peru?, prepared by the organization Water Witness.

Far from correcting this imbalance, the ANA reform has weakened its technical and supervisory role. Instead of strengthening control mechanisms, the Reorganizing Commission's final report proposes further relaxing the processes for granting water use rights.

One of the most worrying measures is the elimination of the mandatory nature of the ANA's technical opinion in certain environmental evaluation procedures. Until now, this opinion functions as a key filter to avoid negative impacts on water sources. But if it ceases to be binding—as the reform proposes—projects could be approved without solid technical support, even in areas where water is already scarce.

Another proposal seeks to transform temporary authorizations for the discharge and reuse of wastewater into permanent licenses. This would reduce periodic supervision over activities that could contaminate already vulnerable sources, in a country facing serious water quality problems. It is also proposed to exempt from sanctions those who have been using water on State land without authorization. Under the argument of fostering formalization, there is a risk of legalizing years of irregular use without any real fiscalization process.

The role of the National Environmental Impact Assessment System (SEIA) is even questioned, calling it a “limitation for farmers.” But it is an important tool that the country has to prevent and mitigate environmental damage. Its weakening would mainly affect users who have the least power to defend their right to water against large projects.

The Reform Also Rearranged Its Allies

The restructuring process of the National Water Authority, initiated in September 2024, also brought a change in its leadership. That same month, Alonzo Zapata Cornejo resigned from the position, and Minister Ángel Manero appointed agricultural engineer Genaro Musayón Ayala, who was also a member of the reorganizing commission, as the new head of the entity.

Until May of that year, Musayón had been a technical advisor to Fujimori-aligned congresswoman Cruz Zeta Chunga, then president of the Congressional Agrarian Commission and the main promoter of a new Agrarian Law to extend tax benefits to the agro-export sector until 2035.

Known as “Ley Climper 2.0,” the proposal could be voted on in August, when the legislature restarts, and has already generated strong criticism for its fiscal impact. According to the Ministry of Economy and Finance, it would imply an annual reduction of nearly S/ 1.85 billion in revenue, which could affect essential areas such as education and security, and weaken fiscal rules.

The Fiscal Council warns that agro-export is already the main beneficiary of this system: it concentrates about 29% of the total tax expenditure, that is, the portion of income that the State ceases to receive due to exemptions, deductions, and reduced rates. In simple terms: for every S/ 100 that the State stops collecting due to these benefits, about S/ 29 goes to the agricultural sector.

Congresswoman Zeta Chunga received at least nine visits from representatives of the Association of Peruvian Agricultural Producers Guilds while putting her bill up for debate. Seven of those meetings occurred between December 2023 and May 2024, when Musayón was still part of her office as a technical advisor. The proposal responds to an old demand from the agro-export sector, which since the repeal of the Agrarian Promotion Law in 2020 has pushed to recover incentives that, they claim, they need to maintain their competitiveness.

When he assumed the leadership of the ANA, Genaro Musayón was not unknown within the institution. In 2022, he was acting general manager and previously held technical positions in local water administrations in Chicama, Pisco, and Mala-Omas. But what had not been publicly warned until now are his disciplinary records. In 2018, the Superior Administrative Responsibilities Tribunal sanctioned him for “adulteration of consumption receipts” to the detriment of the State. Although the Comptroller's Office proposed a four-year disqualification, the tribunal reduced it to two. Musayón completed that sanction between September 2018 and September 2020.

Although he did not agree to an interview for this report, Genaro Musayón has public statements that reveal his approach as head of the ANA. In a meeting with agrarian guilds held in November 2024, he affirmed that the entity “is working on a proposal for mixed licenses for surface and groundwater in dry seasons,” with the objective of “streamlining procedures and facilitating access to usage rights.” An announcement that aligns with what was proposed by the entity's Reorganizing Commission.

A month later, in December, Musayón warned that “we have become accustomed to using only surface water and have neglected the use of groundwater” in the face of drought scenarios. In this context, he has supported extraordinary authorizations to address water emergencies: following alerts in the north of the country, the ANA authorized the increase in groundwater extraction volumes and, in regions like Piura, approved the reactivation of wells. According to Musayón, hydrogeological studies are also being prepared that will serve as the basis for a future National Groundwater Program.

However, specialists warn that this technocratic approach of “resource optimization” can worsen the overexploitation of aquifers, especially in zones with water stress such as the northern and southern coast of the country. The ANA itself has reported that basins such as those of Ica and Piura present a sustained drop in the water table level and are among the most vulnerable due to the intensive use of groundwater. The Comptroller's Office, for its part, has warned that the State does not have sufficient capacities to adequately supervise these uses, due to the shortage of personnel and logistical limitations in the regions.

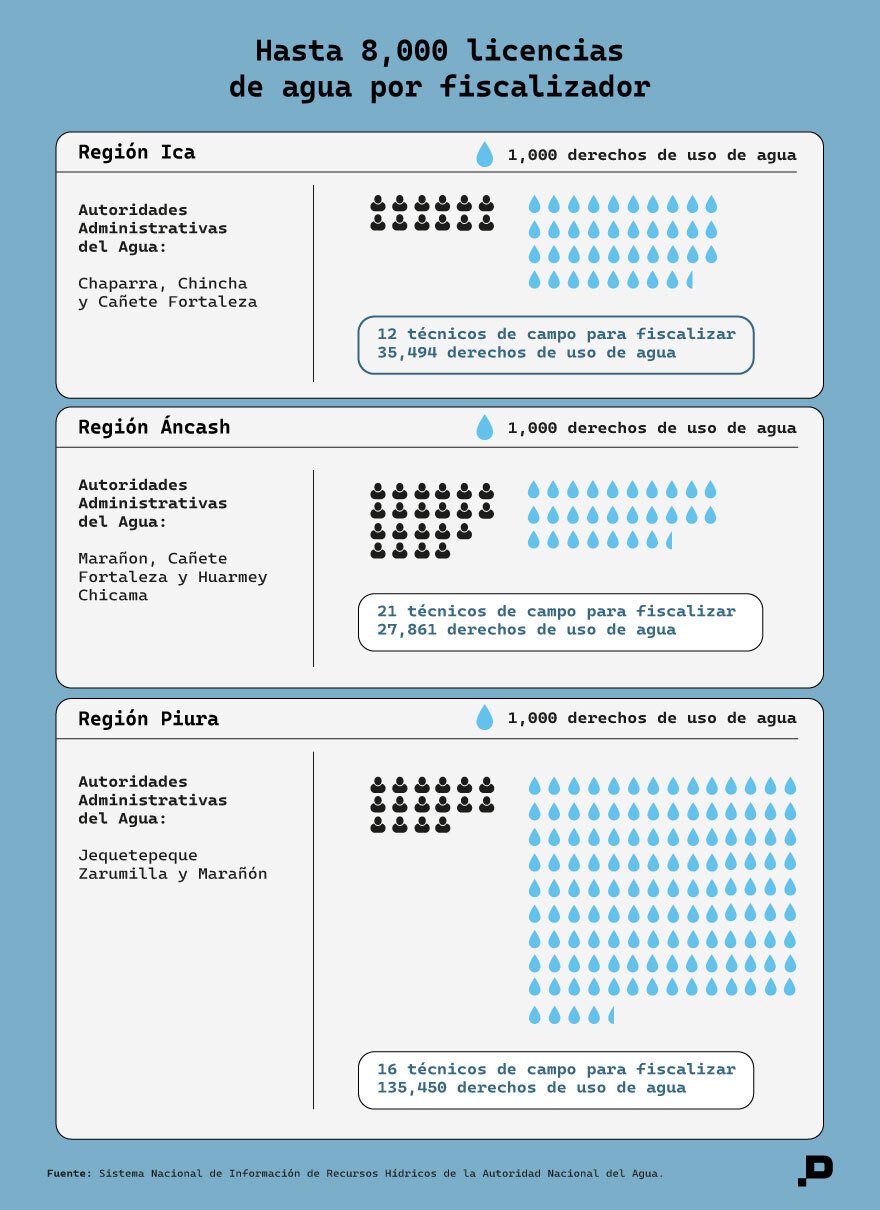

Only 59 Supervisors for More Than 460 Thousand Water Licenses

While processes are being relaxed within the framework of the reform, the National Water Authority faces a critical reality: it has barely 59 field technicians to supervise more than 460,000 water use rights nationwide. These supervisors are distributed among the 13 Administrative Water Authorities (AAA), in charge of management at the basin level, and more than 70 Local Water Administrations (ALA), responsible for smaller areas. On average, each technician would have to supervise nearly 8,000 permits, a clearly unsustainable workload.

Edson Ríos Villagómez, former director of the AAA Chaparra–Chincha, maintains that effective fiscalization requires trained, updated, and well-paid personnel. He criticizes that the Reorganizing Commission did not dimension the problem: “They should have said how many workers are needed to face the operational load of the decentralized bodies. And that has not been done.”

In several regions, the situation is even more serious. In the ALA Ica, only three inspectors must supervise more than 17,000 rights. In the ALA Huaraz, five inspectors are in charge of almost 15,000. The reorganization report itself recognizes that many offices do not reach the minimum necessary technical staff: 14 per AAA and 11 per ALA. High turnover and lack of budget exacerbate the operational crisis.

Added to this is job insecurity. 70% of the personnel work with temporary contracts (CAS or services), which impacts their continuity and autonomy. Román Vera, secretary general of the National Union of ANA Workers, summarizes it this way: “There are colleagues who have to act as technicians, drivers, notifiers, and lawyers. All with low salaries.”

Institutional disorder also affects basic information. The reorganization report reveals that the ANA does not have updated data on how many underground wells are actually in operation or on the total agricultural surface area of the country. Many estimates are still based on the 2012 Agricultural Census. Regional offices admit that they are not clear on how many users or hectares they should be supervising.

Specialist Pavel Aquino points out that part of this information probably exists, but it is not systematized or centralized: “Officials in the decentralized offices prepare physical reports that are then not digitized or uploaded to a platform. Thus, that information is not used. The problem is not only the lack of data but the lack of systematization.”

A Law That Could Open the Water Market

One of the least discussed aspects of the new Agrarian Law bill is that it raises a key modification in water use: allowing user associations to transfer the surplus they manage to save to third parties. This would mark a substantial change in the Water Resources Law, which since 2009 establishes that water is a public, non-commercial good, and that all use must be authorized by the National Water Authority.

According to the current regulation, if a user association—for example, an irrigation board—manages to use less water than it is authorized for, it must report that surplus to the ANA. The entity is responsible for evaluating its redistribution based on technical criteria, prioritizing population supply, ecosystem sustainability, and other uses. The new text eliminates that obligation and allows the associations themselves to decide what to do with that saved water.

In practice, this would open the possibility that this surplus could be sold or transferred to private companies, without a technical evaluation or redistribution process by the State, explains Laureano del Castillo, executive director of the Peruvian Center for Social Studies (CEPES). Although the bill does not mention the word “sale,” the use of the term “transfer” without specific regulation raises concern among specialists about its potential to legalize commercial exchanges over the water resource.

Another proposed change is that farmers can use that surplus even outside the zone of their original license. This would allow its transfer to areas with greater agro-export activity or greater payment capacity. Although it is presented as a way to incentivize savings and efficiency in irrigation, the change introduces a market logic into water management, a shift that has not been part of the public debate and that could alter the management model defined by the current law.

The reform of the National Water Authority and the accompanying legislative proposals mark a turning point in how this resource is managed in the country. Beyond the technical or legal arguments, what is at stake is the State's capacity to guarantee equitable, sustainable, and common-good access to water, in a context of increasing water stress and disputes over control of this essential resource.