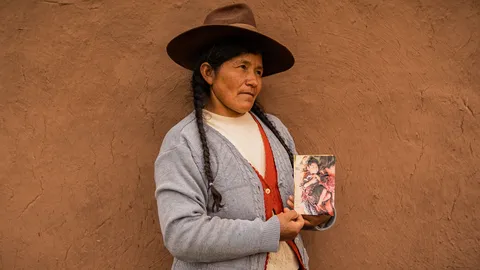

One September afternoon in 2017, Camila*, a 13-year-old indigenous girl, was raped at home by her father. It was not the first time. Over four years she had suffered abuse in silence, fearing that no one else in the family would believe her and that others in her community in Apurímac would cast her out. Two months later, at the signs of an unwanted pregnancy, Camila told her mother what had happened. They decided to seek justice. But they never imagined how Camila’s life and health would be jeopardized further at the hand of the authorities.

The first step was to report the case to the local police. Then, in the company of her godmother, Camila sought a medical examination at a hospital located in a distant town. The staff measured how far the pregnancy had advanced, prescribed folic acid, and told her to attend prenatal checks. What they failed to say was that due to her age and the health risks the pregnancy posed, Camila was also entitled to therapeutic abortion. Even though she was an adolescent victim of sexual abuse, no doctor informed her of this right. Girls and adolescents between the ages of 10 and 14 are four times more likely to die during childbirth than are adult women.

Later, at her community health center, Camila told the staff she wanted to end this pregnancy a rape had produced. But nobody paid any attention. They carried on with the prenatal care. A nurse would regularly visit Camila’s home several times to insist she undertake prenatal checks. On one occasion, the nurse arrived in the company of a police officer, and, as a result, the neighbors discovered Camila’s secret. She plunged deep into depression and dropped out of school. “I want to die,” she told her mother at the peak of her crisis.

Concerned about the situation, a family friend advised Camila’s mother to claim the teenager’s right to a therapeutic abortion. And on December 13, at the Guillermo Díaz de la Vega hospital, she requested voluntary termination of Camila’s pregnancy using therapeutic means. But the response was silence.

Available in cases where the life or health of the pregnant woman is at risk, therapeutic abortion has been legal in Peru since 1924. However, adolescent girls still face several constraints in accessing the procedure and as a result suffer additional physical and psychological harm. A regional study by the NGO Planned Parenthood Global showed that 24% of girls between nine and fourteen years of age who underwent forced pregnancy encountered complications at the time of delivery, such as hemorrhage and infection.

On December 16, after severe abdominal pain and light bleeding, Camila suffered a spontaneous miscarriage. Even before she still could fully come to terms with the awful experience, the Prosecutor’s Office opened an investigation, firstly against her father (who was arrested and later sentenced to life imprisonment) and then, inexplicably and absurdly, against Camila herself. The alleged crime was induced abortion. Accused as an adolescent offender, Camilla went from victim to defendant.

Unfortunately, Camila’s story is that of thousands of abused girls and young women in Peru. Because the law obliges doctors to inform the police and the Public Prosecutor’s Office, those who arrive at medical centers showing the effects of an abortion, whether induced or spontaneous, find themselves the subject of judicial proceedings. Between 2012 and 2018, around twenty thousand girls and adolescents in this situation received treatment at Ministry of Health facilities.

These cases continue even though the Peruvian state has twice been held accountable in international tribunals for having violated the rights of girls and adolescents by denying them access to therapeutic abortion when their health and life was at risk. On television last Sunday—International Day of the Girl Child—the current Minister for Women and Vulnerable Populations, Rosario Sacieta, went as far as saying that the decision on therapeutic abortion was “a matter of conscience.”

Camila’s mother also unsuccessfully lodged an administrative appeal with the National Superintendency of Health. She cited irregularities in the care provided during this forced and high-risk pregnancy, and the failure to respond to the request for a therapeutic abortion. In March 2018, female lawyers from Promsex, an organization that defends sexual and reproductive rights, took on the teenager’s defense, beginning a series of judicial and administrative actions that would end the case against Camila. In July 2019, the charge of induced abortion was dropped. Still frustrated at the indifference shown by local authorities, Camila turned to international bodies to seek justice and compensation.

“She is searching for justice and wants to take the case further because, although the aggressor is already in jail and she will carry on with her life, she does not want other girls to experience what she went through,” says Gabriela Oporto, Promsex Strategic Litigation Coordinator.

Using Promsex’s legal advice, the case report was filed this week with the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. It has the support of Planned Parenthood Global, the Center for Reproductive Rights, and the #NiñasNoMadres (ChildrenNotMothers) movement. This case of sexual abuse of a girl is Peru’s first to be brought before the committee. It aims for the Peruvian state to permit therapeutic abortion and develop procedures to ensure that girls who become pregnant due to rape receive comprehensive attention.

All that remains is for the committee to admit the request and set a hearing date. It has been a long road that Camila has willingly traveled to ensure that the state no longer forces girls to become mothers.

*Salud Con Lupa has changed the name to protect the child’s identity.

The rights that Camila was denied

This case represents violation of a series of rights under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, an international treaty that recognizes the human rights of children that state parties, such as the government of Peru, must respect.

Right to health

Camila was denied access to a therapeutic abortion even though her health and life were at risk.

Right to non-discrimination

Camila was accused of the crime of inducing an abortion even though she had a spontaneous miscarriage.

Right to information

Camila was not informed of the risks of her pregnancy or her right to therapeutic abortion.

Right to life, survival, and development

Camila was exposed to a real and foreseeable risk of maternal mortality and death by suicide.