Janeth Quispe raises alpacas in the indigenous community of Carhuancho, at more than 4,600 meters above sea level, in Huancavelica, in the Andean highlands where almost nothing can be planted and only ichu grass survives. She learned the trade as a child and today, every morning, she takes her herd to the bofedales—those meadows that store water from rain and snowmelt like sponges—to feed her 1,500 animals. Those wetlands, once green almost all year round, now dry out more quickly.

When we accompany her on her route, she shows us her handmade reservoir, which she built alone to maintain the pastures on her land. Before, when the Chonta mountain range was covered in snow, the meltwater would flow down to lagoons and rivers and preserve moisture for months. Now, the white of the mountain is no longer there and, when it finally rains, the water runs off without staying.

"It no longer lasts us the whole year. The climate is already in disorder," she says, her gaze on her alpacas. The young don't manage to survive, the pastures run out too soon and, in the driest months, when the river becomes a thread, she has to carry water in jugs from the springs to keep the herd alive.

In the records of the National Service of Meteorology and Hydrology (Senamhi), this perception has support: before, rains were distributed over several months, which kept rivers flowing for half a year and sustained the bofedales for long seasons. Today, in contrast, precipitation is concentrated in brief periods, more intense and fleeting. As a result, rivers flow for barely three months instead of six and landslides and floods increase.Janeth and hundreds of alpaca herders are worried about the changing climate and also about a project that, over time, has deepened the feeling of abandonment and inequality: the water transfer that diverts part of the water born in these mountains toward the coast.

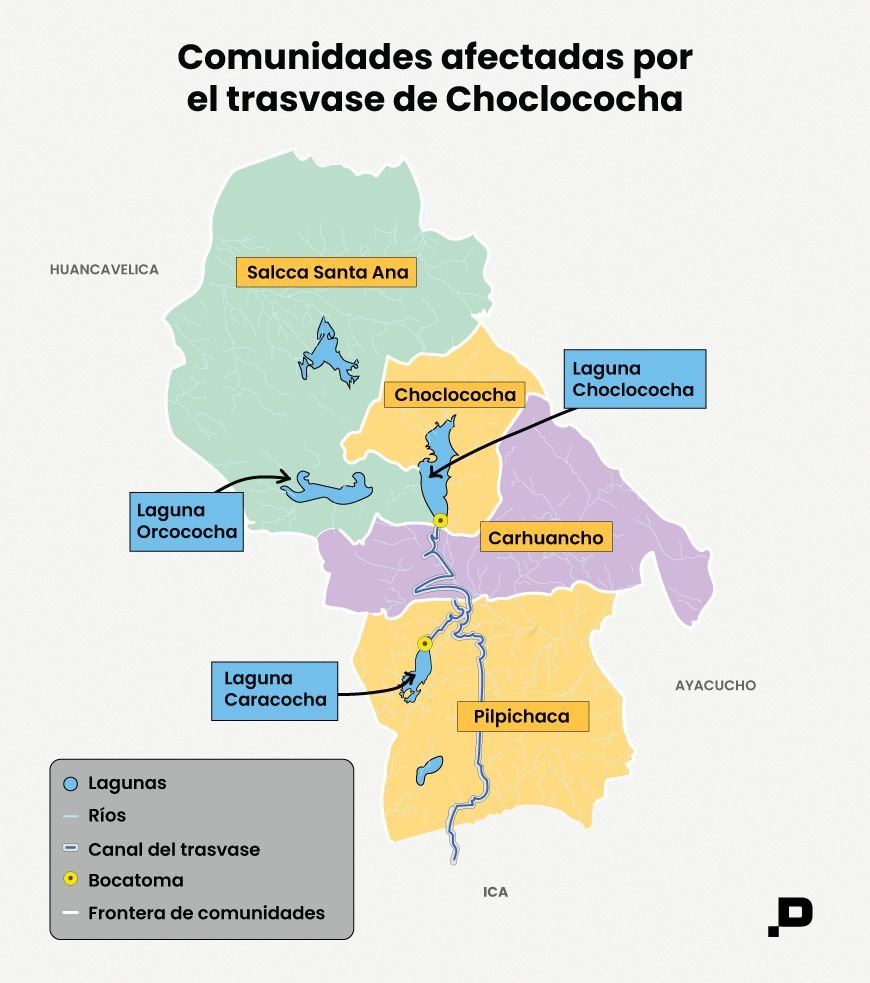

Since 1950, the natural course of waters that flowed down the Pampas River toward the Amazon was interrupted by a hydraulic system that intervenes three high Andean lagoons: Choclococha, Orcococha and Ccaracocha. Dikes and gates retain the water and divert it toward an open canal that, over 53.5 kilometers, crosses the mountain range to Totorillas lagoon, already in the Ica River basin. From there, it descends by gravity to the coastal valleys.

That flow sustains crops of small and large producers, recharges the aquifer—underground freshwater reserve—that feeds more than 2,000 wells of agro-export companies and supplies the population of Ica. Above, in contrast, communities face increasing difficulties in sustaining their lives: water for livestock is scarce, the land becomes less fertile and droughts are longer in a context of climate crisis.

The Tambo Ccaracocha Special Project (PETACC), under administration of the Regional Government of Ica, is the agency in charge of managing this project. Each year it diverts between 10 and 15 cubic meters of water per second, a flow that, if maintained continuously over twelve months, would reach 490 million cubic meters, enough to fill about 200 thousand Olympic swimming pools. However, according to PETACC, in practice the system operates only during some months, so the volume actually transferred has oscillated in recent years between 110 and 120 million cubic meters annually. That amount is equivalent to about 45 thousand Olympic pools per year.

Carhuancho and its neighboring communities—Choclococha, Santa Inés, Santa Ana and Pilpichaca—are in the upper part of the Pampas River basin, right at the start of the transfer. Together they total more than 4,000 inhabitants, mostly Quechua speakers dedicated to raising alpacas and sheep. Over the years, many left: livestock raising wasn't enough, schools were few and their children's future became clouded.

In families' memory, the transfer marked a before and after: floods that swept away houses and pastures, animals that fell into the canal due to lack of protective fences and water that became untouchable, visible only in passing.

Different organizations have confirmed this in reports and diagnoses. In 2007, the Latin American Water Tribunal concluded that the Choclococha to Ica water transfer was drying out pastures and affecting the livelihoods of high Andean communities by not respecting an ecological flow. In 2010, a report by Water Witness International, led by researcher David Hepworth, warned that water extraction from Huancavelica was degrading wetlands and increasing the risk of droughts and floods. In 2014, the Regional Government of Ica itself recognized in a diagnosis the socio-environmental damages and conflict of the project, and an academic study noted that Huancavelica was bearing the costs without receiving compensation.

Between 2015 and 2017, Payment for Ecosystem Services mechanisms were discussed, but never applied. More recently, in 2021, the OECD observed that the benefits of this project are concentrated in coastal agro-exports while the impacts fall on Huancavelica.

In a context of climate change, with increasingly irregular rains and more frequent extreme events, these warnings take on greater gravity: without compensation or restoration measures, Andean communities have been left more vulnerable to prolonged droughts and devastating floods.

The Water Resources Law provides that, when a hydraulic project crosses communal lands or generates damage, it is appropriate to grant compensation or indemnification. In Huancavelica that obligation was never fulfilled, despite it being one of the poorest regions in the country—in 2023, 39.4% of its population was in a situation of poverty, according to INEI—and one of the most vulnerable to climate change, according to the Climate Vulnerability Map of the Ministry of Environment.

"Here the water that goes to the coast of Ica is born, but there is no support from the regional government, nor the national one, nor from the companies that benefit. And we are the ones who take care of this territory," claims Guzmán Llamoca, community member of Salcca, in neighboring Santa Ana.

When in April 2023 the Water Canon Law was approved, in Huancavelica almost nobody knew. To this day, many communities are unaware that it is in force and, where they did find out, the regulation did not generate enthusiasm: it was born bogged down, with objections from ministries that questioned its financing and the lack of clarity about how it would be applied. Added to this is a background of decades of unfulfilled promises—frustrated commissions, a photo-op "water brotherhood," an Ica-Huancavelica commonwealth that barely operates and meetings without results—that has eroded trust.

In Peru, water does not belong to the communities where it originates. The Water Resources Law defines it as a public good administered by the State, through the National Water Authority. Under that principle, the Water Canon was designed: not as payment for water, but as compensation for those who care for watershed headwaters that enable productive activities in other regions. The regulation does not apply to hydroelectric transfers, only to those for agricultural or industrial use.

Law No. 31720 provided that, if a region contributes water used in another for agro-exports, mining or industry, it receives priority investment in return. For this it established this distribution: 25% for district municipalities, 25% for provincial ones and 50% for population centers in the area of origin, with spending directed to agricultural, sanitation and environmental protection projects (not to current expenses).

The process stalled immediately. Congress approved the regulation by insistence despite technical criticism from ministries, and the Executive Branch filed a lawsuit before the Constitutional Court. In February 2025, the Court ratified the validity of the law, recalling that Congress has the power to create new types of canon as long as resources are destined for public investment. It also specified pending tasks: the National Water Authority had to identify the areas of origin and destination of the included transfers, and the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) establish budget criteria for their distribution.

The law itself set deadlines: in 90 days the regulation had to be approved—in charge of MEF and the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Irrigation—and, in addition, that ministry and the Ministry of Environment were tasked with preparing a baseline on the impacts of transfers on communities of origin. As of September 2025, none of this had been fulfilled. The Water Canon is in force, yes, but without real effects.

"They ask us to take care of the water, but here we continue the same or worse because we can no longer keep our livestock well. Where is the development they promise so much if it never arrives?" asks Pelayo Sánchez, president of the peasant community of Choclococha, one of the most affected by floods that forced families to relocate from their original settlement.

The water they cannot touch

In the hamlet of Huaracco, within the indigenous community of Carhuancho, Nemi Achurata questions that, in her own territory, water is treated as an untouchable resource, administered by others, without them being able to decide on its use or access it freely.

"The gentlemen of PETACC are owners of the water: they release it when they want and take it from us when they want. They have told me many times to my face: 'You have no right,'" she assures.

Nemi raises trout to support her family, but has lost thousands due to abrupt changes in flow.

"In one batch 60 thousand trout died on me, in another 30 thousand. Nobody replaced anything for me. I've also lost alpacas. With that I educate my children, but when there's mortality we have no choice but to look for other means. We want to undertake projects, take advantage of resources, but they put obstacles in our way."

Like her, many feel that decisions about the transfer are made behind their backs. The PETACC that Nemi mentions—the Tambo Ccaracocha Special Project—was created in 1990 as part of the state policy of large hydraulic projects to bring water to the valleys of Ica. Initially it was seen as the arm of the State that built dams and canals, but in 2003 its administration passed to the Regional Government of Ica in coordination with the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Irrigation. Since then, the agency acts above all as water administrator, which aggravated conflicts: Huancavelica was left out of management despite the fact that the transfer crosses its territory and communities stopped being heard.

That decision-making power becomes visible each dry season on the coast, when PETACC opens and closes the gates so that water crosses the mountain range and feeds the Ica River. Without that transfer, the natural basin would not be enough to sustain agricultural and population demand, since its own flow is insufficient.

In the highlands, that operation is experienced as unequal treatment. The recent approval in Congress of the new Agrarian Law—which extends tax benefits to the agro-export sector for a decade—reinforced that perception: while the coast receives benefits and water security, in Huancavelica those who care for water sources remain sidelined.

"It's 65 years of a historical debt. The directly affected communities ask for real dialogue to agree on productive projects that compensate for the impact," says Damasco Auris, president of the Federation of Peasant Communities of Huaytará.

The Water Canon Law was approved precisely to address that demand: to allocate exclusive investment to productive projects and water infrastructure in communities of origin. However, since it still does not have regulations, the regulation cannot be applied and its benefits remain in suspense.

From the other side, engineer José Ghezzi, director of the supervision area of PETACC, acknowledges that high Andean communities have borne the costs of this project for decades without receiving compensation. There were attempts, but they were left halfway. He shows a file of signed minutes with specific commitments—repair of homes, small reservoirs for animals, economic compensation—but several were never fulfilled.

"The intention has always been clear: to recognize and compensate," affirms Ghezzi. For him, the Water Canon Law now opens a real opportunity: each cubic meter of water that is transferred to Ica should translate into a monetary value that returns to communities in protection and development projects. That, he emphasizes, must be established in the regulations: how it is calculated, who pays, what it is invested in and who oversees it.

Today there are political and technical bodies that should discuss the future of the Water Canon, but progress is scarce. On the political level is the Huancavelica-Ica Regional Commonwealth (MANRHI), created by governors to coordinate water projects. It was reactivated in 2023 and the following year installed its board of directors, obtained operating budget and began preparing studies for new water planting and harvesting projects. However, so far it has not commented on the Water Canon nor has it implemented projects for communities.

"Not a reservoir, not a ditch to retain water have they made for us. They—those from the coast—receive the benefit, sell their crops, earn money with our water. We are also part of the State and have the right to benefit," claims Hilda Machuca Huamaní, community member of Choclococha.

In the technical sphere, since 2024 the Water Resources Council of the Tambo-Santiago-Ica Interregional Basin has been operating, which brings together authorities from Huancavelica, Ica and the National Water Authority to jointly manage the resource. Its installation occurred several years late: it had been created in 2017 through a supreme decree, in compliance with the Water Resources Law and its regulations, at the request of regional governments that presented a technical file. In September 2025, this Council began preparing its first Management Plan, with participatory working groups. But so far it has not publicly reported what will happen with the Water Canon Law.

The problems of the Water Canon

Instead of reducing conflict, the law that created the Water Canon—promoted by Huancavelican congressmen Wilson Soto and Alfredo Pariona—could open new tensions. Although it was approved with cross-party support from different blocs—Popular Action, Free Peru, Alliance for Progress, Forward Country and Popular Force—that coincidence did not translate into results: so far it has only given rise to a legal and technical debate about how to apply it.

For lawyer Rolando García, from the Scientific University of the South, the central problem is conceptual. In Peru, he explains, canon is applied only to the exploitation of natural resources—mining, oil, gas or forest and fishing resources—not to their use as input in other economic activities.

"Canon is generated with the extraction of the resource, not with the use of the resource to produce something else. In mining, for example, it arises when the mineral is removed from the earth, not when it is refined or jewelry is made. The same should apply to water: it is not extracted to be sold directly, but is used for irrigation or industries. Calling that canon is denaturing the figure that the Constitution itself regulates," warns García.

From his perspective, the Water Canon responds more to a measure of political popularity than to a solid instrument.

"The law sounds good because it promises compensation, but it does not fit the constitutional concept of canon. That makes it weak," he adds.

Experts from the Peruvian Society of Environmental Law (SPDA) share the concern, although from another angle. They recognize the need to compensate communities, but consider that the regulation was poorly designed and runs the risk of not fulfilling its conservation or equity purposes.

"The regulations will be key. If it is not clearly defined how money is distributed, what it is invested in and which sectors should contribute, an opportunity will be lost to strengthen watersheds and guarantee water security," maintain Fátima Contreras and Bryan Jara, of the Environmental Policy and Governance Program of SPDA.

For them, the key is to direct the canon to restoration and conservation projects in watershed headwaters: ecosystem recovery, ancestral infrastructure to retain water in drought season, forestation.

"If the canon ends up in poorly thought-out projects, there will be no real improvement in water security. What is needed is to protect the water sources that sustain both communities and the economy," they affirm.

International experience offers few comparable cases. The most solid examples are in France, Costa Rica and South Africa, where users pay fees per volume of water used and those resources are reinvested in the watershed of origin. In France, this system has operated since 1964 through the Agences de l'eau, regional public agencies that charge fees to industries, farmers and cities, and finance conservation, treatment and river restoration projects with them.

In Costa Rica, since 2006 an environmental canon for water use has been in force: companies and users that extract the resource pay a fee, and what is collected goes to watershed protection and water pollution control programs. In South Africa, since 1998 a comprehensive charging system operates that covers the resource, infrastructure and environmental costs, even with compensation mechanisms for donor watersheds in transfers.

The difference in the Peruvian case is that Law 31720 incorporates a component of territorial justice: it directly allocates part of those resources to municipalities and population centers of the communities where the transferred water originates. That singularity, for some, is a long-awaited reparation; for others, a legal design that could further complicate social conflict over water.

The accumulated years without clear answers or concrete results have only reinforced distrust in Huancavelica communities.

"As long as there is no real support or budget, no more water should be released," warns Pelayo Sánchez, president of Choclococha. "We do what we can: we build handmade lagoons, we care for springs, we plant pastures. But it's not enough. We want the region, the Government and agro-export companies to also work here, in the upper part."

A transfer that feeds aquifers at risk

About 165 kilometers in a straight line from the high Andean lagoons of Huancavelica, the landscape changes radically. After crossing the mountain range and descending to the desert, the Ica valley appears: one of the most productive areas of Peruvian agriculture. On soils that, without water, would be pure sand, endless rows of vineyards, avocado fields and blueberry plantations grow. In recent decades, this fertile strip of desert has become the heart of agro-exports.

According to the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Irrigation, in 2023 alone, agro-exports from Ica exceeded 1.080 billion dollars, with table grapes as the star product, followed by avocado and blueberry. According to the National Water Authority, the region cultivates more than 100 thousand hectares, mostly oriented to export.

But this intensive development is sustained on a water source in crisis. In Ica and Villacurí there are key aquifers that, according to technical estimates, concentrate about 40% of the country's underground exploitation. Even so, they are seriously overexploited: each year more than 200 million m³ are extracted above natural recharge. "That overextraction is equivalent to about 219 Olympic pools per day; that is the magnitude of the problem," explains to Salud con lupa Nick Hepworth, executive director of Water Witness International and co-author of a study published in 2024 on the water crisis in Ica.

As a consequence, agricultural wells must be drilled increasingly deeper and at greater cost to reach groundwater. In some areas depths of 150 meters have already been exceeded.

Here also comes into play the water transfer from Huancavelica to Ica. Agro-export companies often claim they do not depend directly on that resource, and in part it is true: the transferred water does not reach their farms through canals. But the process is more complex. The transfer feeds the Ica River and the valley's irrigation systems; in that route, between 35% and 40% of the flow infiltrates into the subsoil, according to the Geological, Mining and Metallurgical Institute (Ingemmet). That infiltration acts as an indirect recharge of the Ica-Villacurí aquifer, the underground reserve that sustains thousands of agricultural wells on which agro-exports in the valley depend today.

"It is mainly rains that recharge the aquifer, but the transfer plays an important role: it helps keep the underground system from running out and staying alive," explains engineer José Ghezzi.

In parallel, several companies have bet on so-called managed aquifer recharge: infiltration basins that capture water from the Ica River during rainy season and return it to the subsoil. Between 2012 and 2017, the number of infiltration basins multiplied by twenty, going from 41 to 864. In parallel, the surface they occupied also grew significantly: from 22 to 295 hectares, in what is considered one of the largest artificial recharge programs in the world.

Artificial recharge helps, but is not enough to save the valley, warns the latest report from Water Witness International. The Ica River brings so little water that, even with more infiltration basins, it would be impossible to compensate for overextraction. Added to that fragility are risks such as soil salinization and basin clogging with sediments. In this scenario, the Choclococha transfer continues to be decisive in sustaining the recharge of the coastal aquifer that feeds agro-industry. But it does so without effective public control or compensation mechanisms for the communities where the water originates, the study notes.

Faced with that panorama, agro-industry itself is beginning to recognize the magnitude of the problem and the pending debt with Huancavelica. A year ago, a group of agro-export businessmen visited those communities to verify the state of the lagoons and the climate of tension that exists there. Among them was Manuel Olaechea, president of XinérgIca, the association that groups 15 of the main agro-exporters of the valley. In conversation with Salud con lupa, he acknowledged the pending debt:

"Agro-industry does not depend only on the Choclococha transfer, that is an error that has been dragging on for years. But Ica does have a debt with Huancavelica. The project was done without understanding Andean reality. Things as simple as leaving a bridge for livestock or putting drinking troughs... were not thought of. And it is unacceptable that it has not yet been corrected."

The businessman also recalled that the "Water Brotherhood," the alliance that in 2018 the regional governments promoted to bring Ica and Huancavelica together, never worked because it did not involve farmers.

"The problem is that politicians have handled this. If they had left it to us, this would already be resolved."

Regarding compensation, Olaechea assures that among agro-exporters there is willingness to collaborate, although with nuances:

"If the State has abandoned those communities, we cannot do the same. But we are not Santa Claus either: we are not here to give anything away, nor do they need to be given anything. What they need is to be heard."

Currently, a joint project is being developed in Choclococha and Pilpichaca to promote fish farming at altitude, at the request of communities and promoted by XinérgIca. They had already tried before, but the National Water Authority stopped it with the argument that the resource could only be used for agricultural irrigation.

"Why not enable fish farming at altitude, if it can generate real income? At 4,000 meters agriculture is almost impossible, but there are alternatives. And there we do want to help," says the businessman.

Between the water that leaves and the justice that does not arrive

Gathered at the shore of Choclococha lagoon, a group of community members reviews the same claims their parents and grandparents had already made and that still await response: pumps to bring water to dry pastures, mesh to improve livestock, reservoirs to resist droughts and productive projects to strengthen alpaca raising or promote aquaculture. Hilda Machuca takes the floor:

"We have fought for several years. We have gone to Lima, the authorities of Ica and Huancavelica have held hands, but they have never responded to us. Our children stay in the city today, they no longer come. What situation are we in? Here we don't plant anything, we only live with our little livestock."

In Choclococha, talking about the transfer only generates discomfort. Cristian Rojas recalls a concrete case: the mesh fencing that PETACC erected on his land. According to the signed minutes, it had to be built fifty meters above the maximum level of the lagoon to avoid floods.

"Now that mesh fencing is under water. PETACC failed to comply with its commitment and, for us, that is a lack of respect," he affirms.

A few kilometers away, in Carhuancho, Janeth Quispe cleans the handmade reservoir she built to store rainwater. Her voice mixes fatigue and anger:

"We ask for budget for our communities. We want to work with the region and with agro-exporters. We no longer have much water and we need cochas, lagoons, dams in these heights. It is not fair to divert more volumes if there is no compensation."

Faced with a scenario in which the Government and business sector demand greater water diversion from the highlands, communities feel a new threat is opening. What for some is a vital input to sustain a business, for others is the basis of an increasingly fragile life.

The Water Canon Law was presented as a response, but without regulations, it remains a dead letter.

Standing in front of the dried-out hills, Janeth Quispe says it without detours:

"If they don't listen to us, we will keep fighting. Because this land is our life, and we don't plan to leave it."

A pending report to apply the Water Canon

The National Water Authority (ANA) is still preparing the prior technical report that the Constitutional Court requires to identify areas affected by water transfers or impoundments in the country. Without this document, progress cannot be made with regulations or with distribution of the water canon, the law that seeks to compensate regions of origin of the resource.

According to Official Letter No. 0806-2025-ANA-GG, sent on August 1 to the Ministry of Economy and Finance, ANA has formed a working group to comply with this judicial mandate. The task is in charge of the Directorate of Planning and Development of Water Resources, responsible for leading the collection of information on transfer and impoundment projects at the national level. For this, the entity has requested data from ministries, regional and local governments, and other public institutions.

ANA itself acknowledges that preparing the report is a complex process, which requires integrating geographic, technical and social information to determine with precision the territories that must be recognized as affected areas and, therefore, beneficiaries of the Water Canon.