Water is running out in Ocucaje, one of the most arid districts in Ica, where it almost never rains. Matías Taca, a 71-year-old farmer, plants butter beans and squash only in summer, when the Ica River swells and water flows down from the mountains. The rest of the year he buys cylinders for four soles to cook and water what little he can. Like the other 300 small farmers in the area, he lives measuring every drop.

From his plot he watches with concern his largest neighbor: Agroindustrial Beta, one of the main blueberry exporters whose fruit travels to supermarkets in Europe, the United States, and Asia. Since 2021, the company has been drilling into the ground searching for more water to sustain its crops in a valley where each year the aquifer level drops further and old wells run dry.

"We sell what we harvest to Lima markets; we can't do more. They have the means to search for water; we just hope that the little that remains doesn't dry up."

Blueberries—Beta's star product—require about 1,000 cubic meters of water per ton produced. Between 2019 and 2025, the company exported more than a thousand tons worth over 530 million dollars, and its total shipments exceeded 1.2 billion, according to data from the official Infotrade platform.

Each package of fresh fruit that reaches supermarkets around the world carries with it thousands of liters pumped from underground. It's a cost that doesn't appear on any label, but has begun to be measured. The United Kingdom, one of the main destinations for Peruvian agro-exports, funded the study "How Fair is Our Water Footprint in Peru?", the first of its kind in Latin America. The research evaluates how international trade and British investments impact water availability in producing regions like Ica.

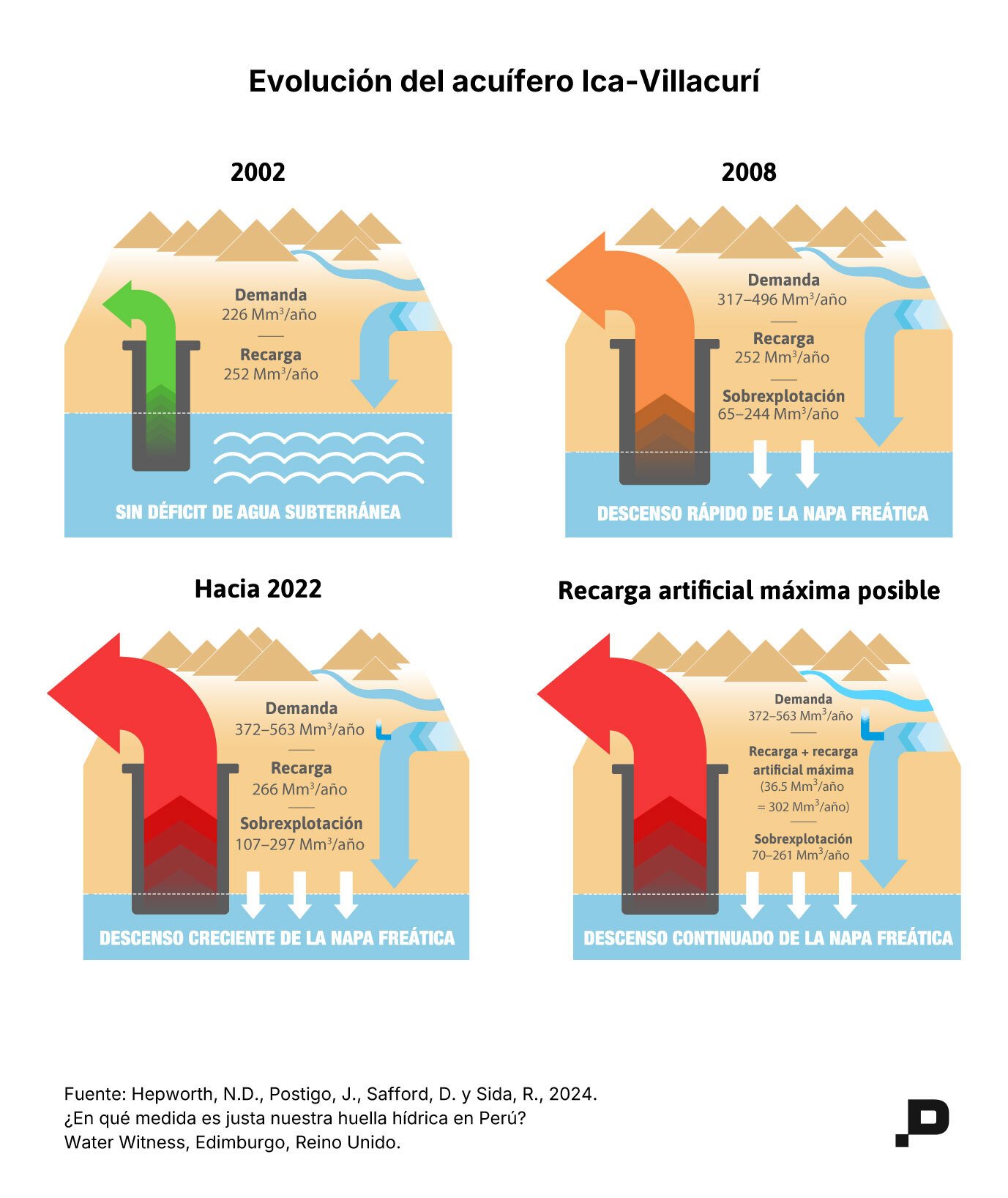

In the Ica valley and the Villacurí and Lanchas plains, the agro-export boom—promoted by the State in the nineties and celebrated as an economic miracle—transformed the desert into a green mosaic of crops. But that prosperity is sustained on underground water reserves that have been in emergency status since 2008, where today the resource is extracted faster than the land can replenish it.

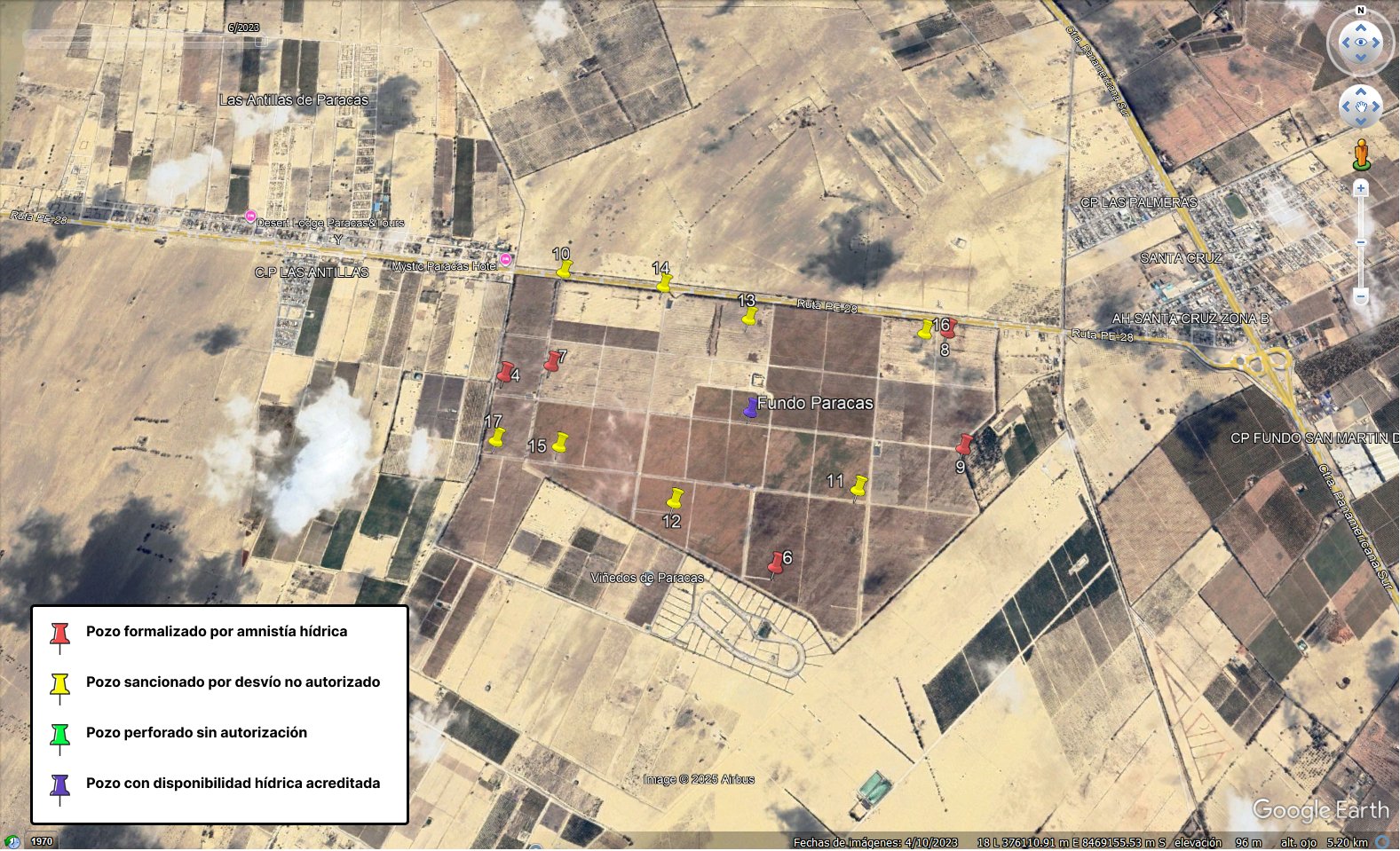

Although several areas of the valley are under ban and drilling new wells has been prohibited for more than a decade, their number has not stopped growing. In fifteen years, it went from 1,700 to 2,116, according to data from the British organization Water Witness based on information from the National Water Authority (ANA). Barely three out of ten have licenses.

In this scenario, more than 200 agro-export companies extract water from the region's underground, although about 30 concentrate the largest cultivation areas—between 400 and 1,500 hectares each. This concentration partly explains the intensity of pumping: the natural recharge of Ica's aquifers—that is, the volume that can be replenished each year without collapsing—is estimated at 266 million cubic meters, but agro-exporters extract between 373 and 563 million, up to double what the underground can recover.

In other words, agro-exports drain between 117 and 325 Olympic swimming pools worth of water each day more than nature can replenish. An imbalance that is depleting Ica's underground reserves.

A Vicious Circle That Legalizes the Informal

Agroindustrial Beta is part of the Matta Group, a conglomerate with fishing, real estate, and agro-export interests that also controls Pesquera Diamante, one of the country's largest. Founded by Víctor Matta Curotto on a small 12-hectare farm in Chincha, the company went from selling laying hens to becoming one of Peru's main agro-exporters.Today it manages 42 farms, 9 packing plants, and more than 5,500 cultivated hectares in Ica, Piura, and Lambayeque.Beta is the third company with the most underground water use rights in the country, according to National Water Authority records. Between 2005 and 2025, it went from having 5 to 256 rights, making it a major user of underground water for the production of blueberries, grapes, pomegranates, avocados, and asparagus destined for the world's most demanding markets.

But that formal power over water contrasts with what happens on the ground.

In 2021, Beta acquired the Santa Ana and Viña Vieja Lote 01 properties in Ocucaje, an area with a special regime that since 2017 has imposed limits on the use of overexploited aquifers. There, all drilling must be carried out under permanent supervision by the National Water Authority.

However, in 2022 inspectors found two wells drilled without authorization, 35 and 20 meters deep, equipped with pumps, generators, and newly installed pipes.

The company was fined S/ 51,603, although it appealed arguing that the wells existed before its arrival. ANA's technical reports, however, documented active machinery and ongoing works: evidence that the drilling was recent.

Matías Taca, a farmer in the area, remembers when the machines began drilling near his plot.

"They made the wells, but it didn't turn out as they expected. The water was salty. What good is a salty well?"

Even so, Beta did not give up. In July 2023 it obtained authorization to explore two new wells, and in April 2024 ANA granted it water accreditation for ten more in the same area. Although this permit does not yet authorize it to drill or extract water, it opens the way to request use licenses in the future.

What this investigation reveals about Beta is not an isolated incident. It reflects how, with the tolerance of the National Water Authority, an extractive model has been consolidated in Ica that, far from stopping, deepens each year, sustained by symbolic sanctions and flexible legal frameworks that allow water overexploitation to continue under an appearance of legality.

The milestone that consolidated this practice was the water amnesty approved in 2015, which allowed the regularization of informal wells, even in areas where underground reserves were already at their limit and under ban due to emergency. Among those favored were the valley's 30 main agro-exporters, including Agroindustrial Beta, Campos del Sur, Agrícola Don Ricardo, Agrícola La Venta, and Agrícola Chapi.

Supreme Decree No. 007-2015-MINAGRI established an exceptional regime that allowed users with unauthorized wells to obtain temporary permits while processing their formalization, paying a fine calculated per irrigated hectare.

In aquifers in emergency status—such as Ica, Villacurí, and Lanchas—the decree set a payment of 0.5 UIT for up to five hectares and an additional 0.1 UIT for each extra hectare.

Specifically, Beta legalized 15 informal wells in the districts of Paracas and Santiago, which comprise these underground basins. It paid fines totaling S/ 169,316, an amount well below the real value of the water used. Thus it obtained official recognition to continue operating in areas where drilling was prohibited.

In all cases, the company acknowledged having extracted water from underground without a license to irrigate grape and asparagus crops on properties between 20 and 60 hectares. The fines imposed ranged from S/ 8,500 to S/ 23,700 per well.

"The authority should not limit itself to imposing economic sanctions," warns Pavel Aquino, water resources expert and former coordinator of environmental evaluation at the National Water Authority. "The response was to seal the informal wells, estimate the damage caused, and charge companies for the benefit obtained from that improper use of the resource. Only in this way would real compensation be achieved for the harm to the State."

"In a ban zone, water is gold," he adds. "It's not the same a cubic meter in the Amazon, where it's abundant, as a cubic meter in Ica. If you multiply that volume by day, by week, by year, you're talking about millions in income generated by water use."

The magnitude of the problem has been analyzed by the United Kingdom, which commissioned the study from researchers at Indiana University (USA), the Peruvian Center for Social Studies (CEPES), and the NGO Water Witness International. ANA itself and the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Irrigation (Midagri) participated in this process.

Its findings, presented in the report "How Fair is Our Water Footprint in Peru?", published in December 2024, reveal that in almost fifteen years, the irrigation surface for agro-exports has expanded by more than 10,000 hectares, most of it on land that was previously desert.

It's difficult to calculate the total water demand in the valley, since extraction rates from illegal wells are not reported. The National Water Authority's most recent estimate—373 million cubic meters per year in 2017—has become outdated. However, historical surveys by ANA itself and hydrological modeling raise that figure to 483 million, while the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)—which evaluates public and environmental policies—calculates 563 million cubic meters annually, which better reflects the real pressure on the resource.

Although ANA has recognized the rapid depletion of underground water, sectors within the State itself and the business community have attempted to discredit the report.

"We've been told that our study is alarmist or biased, that it uses unauthorized data. It's worrying, because it shows how the severity of the problem is still being denied. Solving it requires acknowledging the facts and making decisions based on evidence, not on interests," warns Nick Hepworth, executive director of Water Witness International.

The Change in the Crop Map

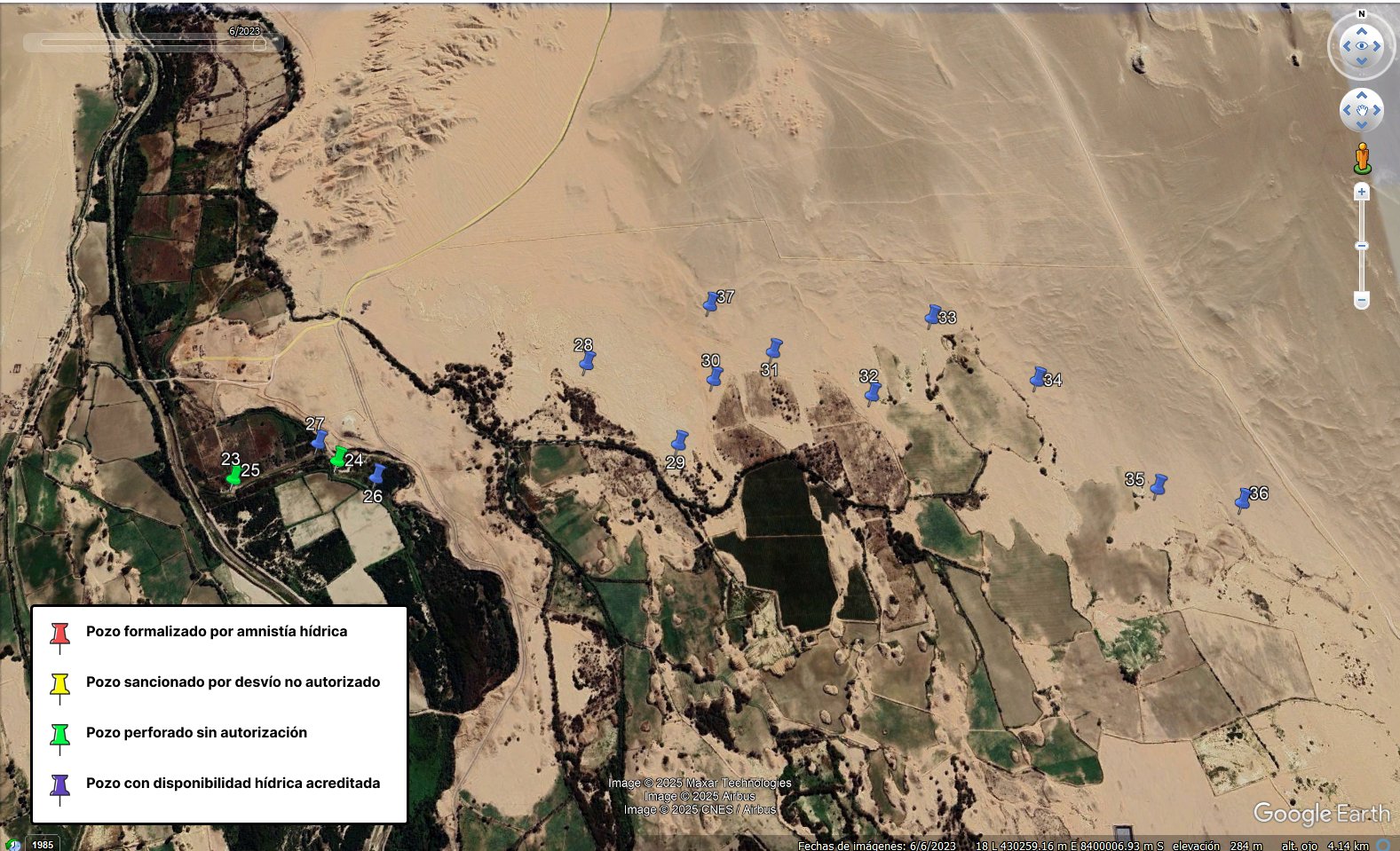

The landscape of the Lanchas plains summarizes Ica's transformation: water hides more than thirty meters down and, when it appears, it's salty. Small farmers plant only what resists; large companies abandon dry wells and change to crops that promise profitability, although they continue drinking from the same exhausted aquifer.

Pascual Yaulicasa lives there, an 81-year-old farmer who arrived in the eighties fleeing violence in Huancavelica. On his plot at the San Juan Bautista Farm he grows only paprika, which he sells to a foreign contractor.

"You can't plant anything else because it needs more consumption," he says. "Before I planted corn and alfalfa, but because of the water we had to change."

Pascual is part of the Lanchas Area Farmers Association, where 28 small producers face the same reality: wells that sink each year and fields that shrink with drought. To irrigate he uses what little remains in his well; to drink, he depends on water that arrives in cisterns sent by the Municipality of Paracas, which in return maintains oxidation ponds—artificial lagoons where wastewater decomposes in the open air—on his land.

A few meters away, the Paracas Farm, belonging to Agroindustrial Beta, has looked abandoned for two years.

"All their farm is dry, that's why they left it," Pascual recalls.

In this area, Beta formalized six wells thanks to the water amnesty. It was also sanctioned for diverting water from eight others without permission. An inspection by the Local Water Authority of Río Seco, in 2012, found a six-inch pipe connecting two plots—one of them acquired by the company the following year—to irrigate them with unauthorized flow. The infraction was fined in 2013 with S/ 37,000 and confirmed in 2016 by the Water Disputes Tribunal, in a territory under ban since 2008 due to high water stress.

Beta, like other agro-exporters in the valley, pushed its wells to the limit and then went out to search for water where it still remained. The company installed technified irrigation and changed crops to adapt to the water emergency, but none of that stopped the aquifer's decline. What happened with the Matta Group's agro-exporter was repeated in many other companies, marking the breaking point of an agricultural model born with the asparagus boom and sustained today with grapes, blueberries, and avocados.

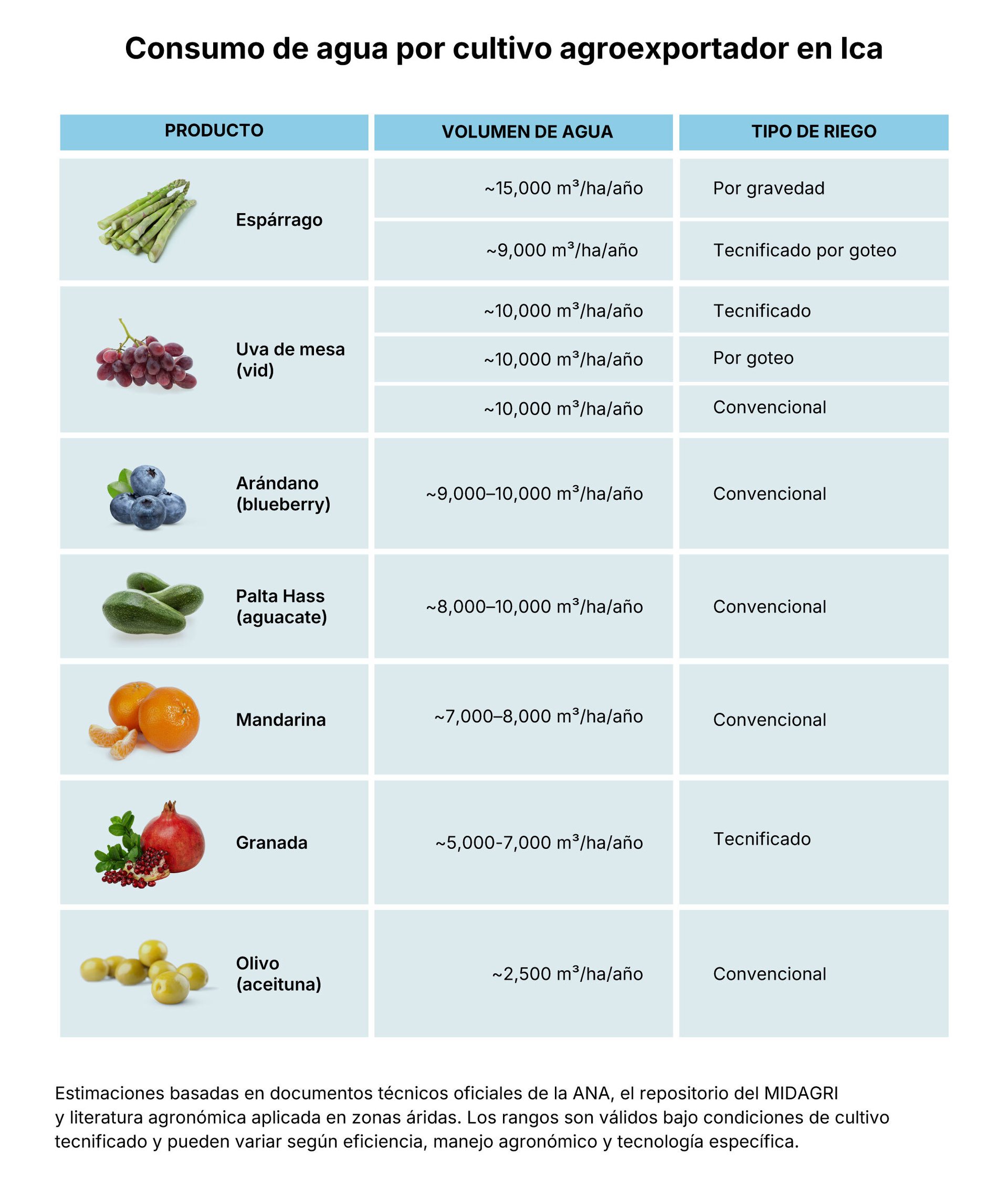

For more than a decade, asparagus was the emblem of the "agro-export miracle": the crop that turned the desert green. Thousands of wells and irrigation networks fed that illusion of abundance. But the cost was enormous. According to research by the University of the Pacific, each hectare of asparagus consumed between 9,000 and 15,000 cubic meters of water per year, depending on the type of irrigation. In a valley without rain, that thirst was impossible to sustain. In 2012, the National Water Authority was already warning of its extremely high water footprint, especially in Villacurí and Lanchas.

When water began to become scarce and the international price of asparagus fell, the valley's companies chose to diversify. The global boom in table grapes, blueberries, and Hass avocados opened new opportunities. According to the National Agrarian Health Service (SENASA), Ica went from depending almost completely on asparagus to leading national grape production and rapidly expanding its fruit crops.

Agroindustrial Beta embodies that transformation: its own reports show how it expanded its portfolio, from the asparagus that drove its initial growth to the production of avocados, grapes, and blueberries, a formula to maintain presence in global markets.

But the change in crops did not relieve pressure on the aquifers. The National Water Authority estimates that a hectare of blueberries consumes about 11,500 cubic meters of water per year; table grapes, between 7,000 and 10,000; and Hass avocados, up to 20,000 in desert areas. The agricultural map evolved, but the thirst remained the same.

According to Nick Hepworth, director of Water Witness International, the paradox is that often the crops presumed to be most efficient are the ones causing the most problems. In the old flood irrigation systems, part of the water returned to underground and helped recharge it. Drip irrigation, on the other hand, delivers water so precisely that plants absorb it all, leaving nothing to replenish reserves.

"Without effective regulation that limits water use according to its real availability," warns Hepworth, "the most profitable crops, like blueberries, grapes, or asparagus, are the ones that most rapidly deteriorate the aquifer."

All crops, he adds, could be sustainable if there were a balance between the water extracted and what is returned to underground. But in Ica that balance is far from being achieved.

"Overexploitation has degraded water quality and reduced its availability, feeding competition among users," warns engineer Gustavo Echegaray, former secretary of the Ica Human Rights Committee. "Ica is living a race to the bottom: only those with resources or influence will be able to continue accessing good quality water."

The Responsibility of Consumer Countries

"Here we use a lot of water so the world can have our fruits, but the situation is catastrophic. When you eat grapes, blueberries, asparagus, or avocados, remember where they come from… and think of Ica, think of thirst and exploitation," said an agricultural worker who asked to keep her name confidential because she still works for an export company.

Despite this, few countries consider the water impact of what they consume. In 2021, Peru and the United Kingdom signed the Glasgow Declaration on Fair Water Footprint, a commitment so that international trade does not deplete the resources of supplier communities. But the findings of the study "How Fair is Our Water Footprint in Peru?" show the opposite: part of British consumption depends on aquifers on the verge of collapse, like those in Ica.

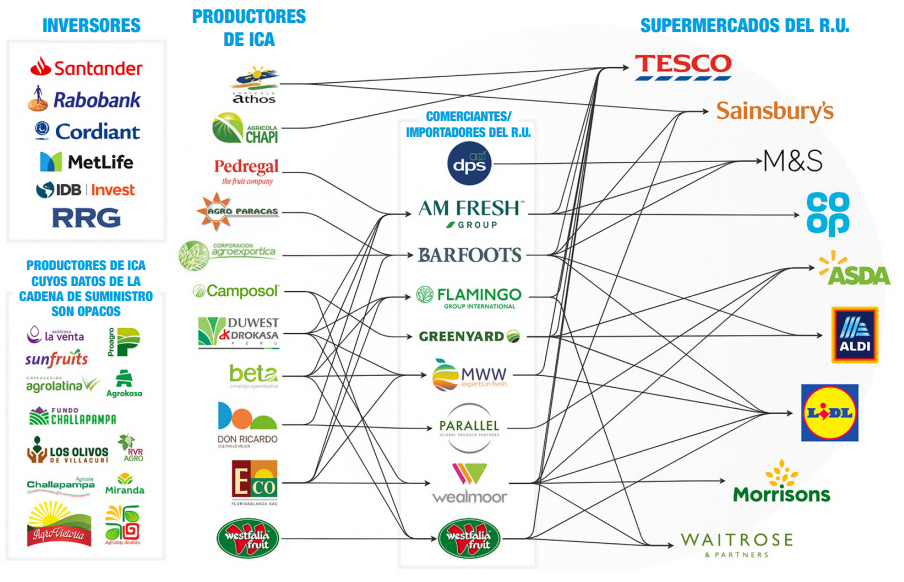

For more than a decade, the main British supermarkets and importers—Tesco, Sainsbury's, Asda, Aldi, Lidl, Co-op, Waitrose, Marks & Spencer, and Worldwide Fruit—have been supplied with fruits and vegetables grown in the Ica valley.

The commercial link has not stopped growing. Since 2010, Peruvian agricultural exports to the United Kingdom increased by more than 1,000%, driven by trade in grapes, avocados, and blueberries, reaching 314 million pounds sterling (almost 393 million dollars) in the 2022–2023 period.

This boom was consolidated with the entry into force of the Trade Agreement between the Andean Countries and the United Kingdom, signed in 2021, which facilitated the exchange of agricultural goods, although without incorporating environmental safeguards to ensure sustainable water use.

For Nick Hepworth, executive director of Water Witness International, that is precisely the blind spot of current trade policy:

"The water crisis developing in Ica was identified and understood a long time ago. All parties involved, including the supermarkets that buy the products, have been aware of the unsustainable nature of water use for at least fifteen years. What's worrying is that no effective measures have been taken to stop a model that everyone recognizes as unviable. It's like watching a car crash in slow motion: everyone sees it coming, but no one brakes. The tragedy is that so many people, companies, and a good part of the Peruvian economy will suffer the consequences."

Salud con lupa requested interviews in October with all the British supermarket chains mentioned in the study through emails with attached questionnaires, but none responded.

However, supermarkets are not the only ones involved. The agro-export model that sustains this relationship has also been financed by international commercial and development banks—including Rabobank, Santander, CAF, IDB Invest, and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank—which have backed agricultural expansion projects even in areas declared under ban due to water overexploitation.

The study warns that, although these entities have environmental, social, and governance policies that require them to prevent harm and respect human rights, in practice there is a gap between their commitments and reality: investments continue flowing to regions where aquifers are depleted and many communities lack safe access to drinking water.

These warnings are not new. In 2009, the Drop by Drop report—also funded by the British government—warned that the expansion of intensive irrigation for export was depleting the aquifers of the Ica region, the country's largest, and generating severe impacts on cities and ecosystems. Fifteen years later, the new assessment confirms that this risk became reality: Ica's underground water reserves are at their limit.

Insufficient Recharges and Voluntary Seals

None of the measures addressing Ica's water crisis have managed to contain it. The law prohibiting drilling new wells is violated, artificial recharges barely compensate a fraction of extracted water, and sustainability seals remain voluntary commitments without real verification.

"Nothing has managed to stop unsustainable water use patterns," explains Eduardo Zegarra, principal researcher at the Group for the Analysis of Development (Grade), "because these responses have focused on increasing supply, not reducing consumption."

Large companies—including Beta, Agrícola Don Ricardo, Agrokasa, Santiago Queirolo, Agrícola Chapi, and El Pedregal—invested in artificial aquifer recharge, diverting river water during rainy season to infiltration ponds. According to data from the Underground Water Users Board (JUASVI), the number of these ponds went from 5 in 2015 to more than 25 in 2023, with ANA's endorsement.

Although this practice is seen as partial compensation, results remain minimal compared to the level of overexploitation.

"Even if all the average annual flow of the Ica River were captured and infiltrated underground—a physically impossible hypothesis—only between 10% and 30% of the current deficit would be compensated," explains Julio Postigo, professor in the Geography Department at Indiana University. "Added to this are other obstacles: the lack of suitable land to expand the ponds, high soil salinity levels, and the accumulation of sediments that obstruct infiltration."

"Without reducing the volume of extracted water, no strategy based solely on artificial recharge can reverse the aquifer's depletion," warns Postigo.

Another measure by agro-exporters has been incorporating so-called sustainability seals: private or voluntary certifications that promise to endorse responsible water use. In Ica, 34 companies have GlobalG.A.P. certification, three have the AWS (Alliance for Water Stewardship) standard, and a still undetermined number have the Blue Certificate, granted by the National Water Authority.

Each of these accreditations has a different scope. GlobalG.A.P. certifies good agricultural practices, including water use efficiency and license compliance. The AWS standard evaluates sustainable water management at the farm or company level, considering its impact on the entire basin. And the Blue Certificate seeks to recognize major users who measure their water footprint, promote efficiency, and implement reuse projects.

However, the study "How Fair is Our Water Footprint in Peru?" indicates that auditors found that several certified farms continue expanding their production and obtaining new extraction permits in areas under ban since 2008, promoting the construction of recharge ponds as good practices, but without modifying real demand or reducing irrigation surface.

Additionally, in audit reports, certified companies maintain that their operations do not affect access to drinking water, despite official data showing a continuous decline in the water table and communities where wells have dried up or water is salty.

For example, Agroindustrial Beta has maintained GlobalG.A.P. certification for more than a decade, supplemented with the GRASP (social responsibility) and SPRING (sustainable water use) modules. However, its operations are carried out in areas under water stress, where it has expanded its cultivated surface and formalized wells under the water amnesty policy.

These recognitions, presented to investors and supermarkets as signals of sustainability, do not necessarily reduce pressure on the aquifer. In one of the most overexploited basins on the planet, they may end up functioning more as a reputation strategy than as an environmental solution.

"Being efficient doesn't mean being sustainable," acknowledges Manuel Olaechea, president of XinérgIca, which groups fifteen agro-exporters in the Ica valley. "I can use little water, but if there's less and less each time, that's not sustainable."

Olaechea, who also leads the Business and Human Rights chapter of the Ica Chamber of Commerce, participated in the study on water use in agro-exports, although he disagrees with part of its results.

"In this valley we all know there are companies that make illegal wells, that abuse water and don't pay taxes. How many of those are named in the study? None," he questions. "On the other hand, those of us who are visible and comply with regulations are pointed out."

Olaechea maintains that the most scrutinized companies, including his own, are promoting recharge projects in the upper part of Huancavelica together with Campos del Sur, Vanguard, Agrícola Chapi, and El Pedregal.

"I'm not saying the study is false: there's a reason we're doing recharge and building wells for population use," he explains. "But the calculations aren't exact. If a company has a license to extract a million cubic meters, ANA assumes it used all that volume, even if that's not the case. With those assumptions, the results don't reflect the aquifer's reality."

"The real problem isn't how many wells exist, but how many hectares are cultivated," he summarizes. "There are small farmers who recharge more water than they consume, but we're all measured with the same yardstick. What we need is a firm hand to order water use and studies that serve to solve it, not just to diagnose it."

Reversing the Trend

If Ica wants to recover its water balance, recharge ponds and sustainability certifications are not enough. The study on the valley's water footprint warns that each year at least 200 million cubic meters of water are extracted more than the aquifer can replenish, an overload that threatens to deplete its underground reserve.

"Overextraction has already surpassed the equilibrium point and, if demand is not reduced, the system will continue collapsing," explains Julio Postigo, geographer at Indiana University and study co-author.

The researchers point out that change must come from the consumption side: closing illegal wells, measuring all extractions, and reviewing licenses to adjust them to real recharge limits. They also propose reducing irrigation with underground water in the most intensive crops and creating a shared management space among farmers, communities, companies, and authorities that establishes clear goals to recover the aquifer.

On the economic front, they recommend reviewing water tariffs—today well below their real cost—and allocating those resources to monitoring, control, and basin restoration.

"No strategy based only on increasing supply, like artificial recharge, can reverse the deterioration. Without reducing extraction, the aquifer will continue falling," summarizes Postigo.

If nothing changes, Ica could become the clearest example of an agricultural model that advanced without measuring the limits of the water that makes it possible.

The Silence of Agroindustrial Beta

On August 20, Salud con lupa requested Agroindustrial Beta’s response regarding this report. At the company’s request, a questionnaire was emailed to its Social Responsibility and Communications office, but no reply was received. On August 26, we attempted to deliver a formal letter requesting comment at its San Isidro offices, where staff refused to accept it. As of the close of this report, the company had not responded.