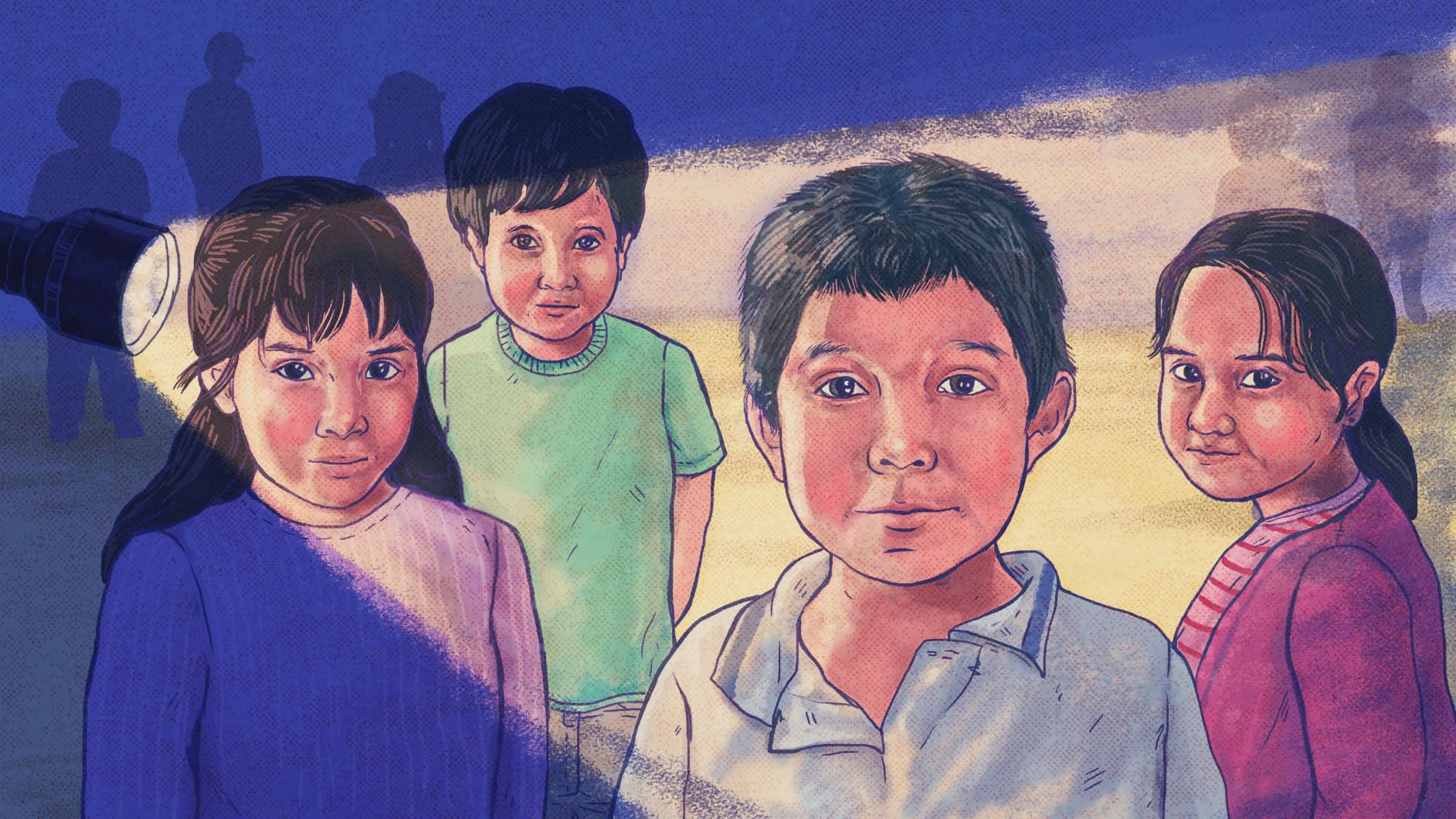

By this point in the pandemic, many of us have lost family members, neighbors, or work colleagues to the coronavirus. This contagious disease has killed more than 120 thousand Peruvians in just one year, more than double the number of victims left by the two decades of internal armed conflict. Yet the greatest damage is found not in the health statistics published each day in the news media. It lies, instead, in the thousands of children and teenagers left orphaned, their homes devastated. The virus is leaving its fingerprints in ways we cannot yet fully measure.

This year, in an attempt to ease the hardship for these orphans, the government introduced a 200 sol monthly payment that each will receive until becoming an adult. The total number of beneficiaries is not yet known. The next government will have to develop comprehensive programs that aim to repair the mental health of an at-risk generation and guarantee its education and financial security. Many are already facing the emotional consequences. They are the most likely to drop out of school and the most exposed to violence in broken homes. Financial assistance is one kind of support, but there needs to be more.

“We need national reforms that include schools which are open and able to find answers for this population. Schools are the places that the youngest children have lost in the pandemic. But they were more than just learning centers: they were spaces where [children] learned to share their feelings,” says Dr Rachel Kidman, a researcher at Stony Brook University in the United States, where she carried out one of the first studies in that country of children orphaned by Covid-19. Kidman’s report points out that children who lose a parent run a heightened risk of accidental death or suicide. They can also suffer trauma and depression and receive poor grades, with the consequences lasting into adulthood. Similar studies do not yet exist in Peru.

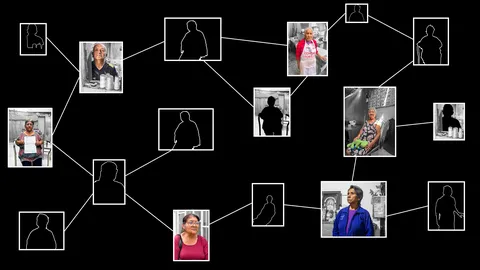

To better understand the problem, we have begun to document the side effects these children and teenagers are experiencing. Our Growing up without parents series begins with three reports. These first stories highlight the barriers to accessing the orphan pension and the urgent need for mental health services, the latter a problem authorities are reluctant to discuss but which can be solved by additional resources to fund more psychologists in schools and community centers. We also describe the conditions prevailing in temporary refuges that receive orphans whose families are unable to look after them.

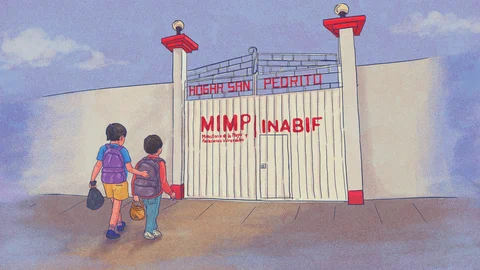

At the moment, the focus is on delivering the pension. “We have to make sure we leave no child behind,” says Carolina Trivelli, the former minister for social inclusion, in reference to this financial assistance. Whilst the money goes to the person with custody of the child, the state also has a role in assessing whether the family is best placed to assure the child’s development. If not, an Inabif shelter provides a caring and safe alternative. However, the facilities must be staffed by trained professionals who can help these children deal with loss and provide the company and warmth the pandemic has robbed them of.