The series "Invisibles" has the support of the

It all started with a question that kept coming up in our team meetings: Why is it so common for older adults to be excluded from Pensión 65 without any explanation? To understand this, we had to look closely at the system that decides who receives support from the Peruvian government. It’s a system that merges databases, surveys households, runs scores through an algorithm… and if the numbers don’t fit, people get excluded.

This system combines field data with administrative records and includes an automated component that calculates a household’s level of poverty. But if it’s fed with incomplete or misinterpreted information, it can make unfair decisions that directly harm those who need help the most. The algorithm also has serious limitations in detecting extreme poverty in urban areas like those in Peru, where elderly people living in neglect or precarious conditions are not always visible in a form or database.

Except for our colleague Jason, who is a computer scientist, none of us had previously investigated an algorithm used in social policies. We learned along the way: submitting public information requests, reviewing regulations, interviewing experts, and cross-checking data with personal testimonies.

That’s how Invisibles was born—an investigation that combined technical evidence with human stories to understand what happens when an automated system stops seeing people. Here, we share how we carried out the project, what tools we used, and what we learned along the way.

Why this story?

The motivation came from a growing number of similar complaints appearing in regional media, on social networks, and at ombudsman offices: older adults who went to the bank to collect their pension and were told just one sentence—“No deposit. Check your status.” No one called them. No one explained. They had simply stopped existing in the system.

Over several months, we discovered that many of these exclusions were not due to real improvements in people’s living conditions, but to structural flaws in Peru’s Household Targeting System (SISFOH)—the tool the government uses to classify households by poverty level.

We were drawn to this story not only because it revealed serious failures in a public policy, but also because it shows how automated systems—even if they’re not advanced artificial intelligence—can reinforce the very inequalities they claim to fix, if they are not designed, updated, or adjusted with fairness and social reality in mind.

SISFOH is based on the Proxy Means Test, an algorithmic model that estimates monetary poverty using indirect indicators like housing type, access to basic services, or ownership of certain goods. This methodology, promoted by the World Bank since the 1990s, was adopted in Peru in 2004 to better target public resources. But over time, it has shown serious limitations—especially in urban settings where many forms of hardship can’t be seen in a form or electricity bill.

When it comes to older adults, the system struggles to detect situations of neglect, dependency, or vulnerability that don’t appear in administrative data. Instead of prioritizing those who need support the most, it often leaves them out. And in a country with outdated information, deep inequality, and limited transparency, automating decisions about poverty is not neutral—it can be deeply unjust.

Our Hypothesis

The targeting system was prioritizing the prevention of inclusion errors—avoiding giving benefits to those who don’t need them—but it was doing so at the cost of committing thousands of exclusion errors: leaving out people who truly need support. This got worse after the pandemic, which drastically changed the lives of millions of households, especially in urban areas. But the system didn’t capture those changes—nor has it adapted to them.

In addition, the algorithm evaluates the household as a single unit, not the individuals within it. This means that if an older adult lives with relatives who have some income or own certain assets, the system may assume that person doesn’t need help—even if they are abandoned, have no income, and receive no care. On paper, they are not extremely poor. In real life, they are.

What Did We Do?

We formed a core team of three: Fabiola Torres, Jason Martínez, and Rocío Romero. We worked with illustrator Ro Oré on visual graphics, Álvaro Cáceres on video production, and Max Cabello on photography. From the beginning, we defined a dual strategy: one investigative angle focused on the SISFOH algorithm, and another centered on public service—to fill the information gap faced by thousands of older adults who don’t understand why they lost their pension or how to get it back.

Our methodology included:

- 16 public information requests submitted to the Ministry of Development and Social Inclusion (MIDIS), the Pensión 65 program, and the OFIS (Focalization Office), using Peru’s Transparency Law. This gave us access to national databases of beneficiaries, suspended and reinstated individuals, and those on the waiting list between 2020 and 2025.

- Expert and technical sources: We interviewed specialists with deep knowledge of the design and operation of SISFOH, and reviewed academic research that provided context and possible alternatives to the current model.

Carolina Trivelli, economist and former Minister of Development and Social Inclusion (2011–2013), promoted the creation of SISFOH and has closely followed its evolution. She explained why the system is not designed to detect individual vulnerabilities such as abandonment, and why many older adults are left out despite needing support.

Lorena Alcázar, senior researcher at the Group for the Analysis of Development (GRADE), has evaluated how Local Targeting Units (ULEs) operate and the quality of the data they collect. Her findings on systematic errors in socioeconomic forms helped us understand how decisions based on incomplete or misinterpreted information get passed on to the algorithm.

Angelo Cozzubo, a Peruvian expert in public policy and data science at NORC at the University of Chicago, offered a critical view of SISFOH’s technical logic. He warned that the system neither prevents poverty nor anticipates vulnerability, and that new data governance is needed for a fairer and more agile targeting process.

Jonathan Clausen, researcher at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, was not interviewed directly, but his study—published in The Journal of the Economics of Ageing (June 2025)—was key to our analysis. He proposes a multidimensional poverty index tailored to older adults, covering seven areas: health, education, employment and social protection, social connectedness, housing, water and sanitation, and energy. This approach highlights the limits of a system based solely on monetary indicators.

We also spoke with SISFOH officials, some off the record, who shared insights and concerns about how the system works in practice. Despite multiple formal attempts, neither MIDIS nor the Pensión 65 program responded to our interview requests or written questions.

- Review of laws and technical documents, including MIDIS resolutions, World Bank reports, and ongoing policy reform proposals.

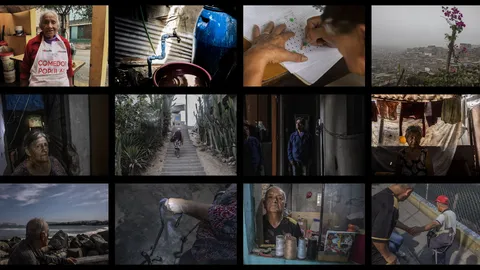

- Field reporting of real-life cases in urban and rural areas such as Lima, Ucayali, and Arequipa, which helped ground the investigation beyond abstract algorithms. We went out to listen, verify, and understand how unjust exclusions play out in everyday life. We saw how an automated decision can cut off the only income source for an older adult—and with it, their access to food, medicine, or basic services.

We documented exclusion cases that lasted years, like those of Rosa, Rosalía, and Teodomiro, who were eventually reinstated after long appeals. These stories showed us that the errors were not isolated—they were structural. And they also revealed something even more important: that the algorithm fails not just because of missing data, but because of poor data collection and the lack of trained, qualified staff in ULEs and local field offices.

That’s why this project combined technical analysis with a service-oriented approach. Because it’s not enough to expose what’s wrong—we also need to explain how the system works, what rights people have, and what they can do if the State has left them out. This practical component was just as important as the investigation itself. And it’s a model that other journalists can adapt if they want their reporting to have a direct impact on affected communities.

- We analyzed the flaws in the algorithm and the socioeconomic form, showing how small details—a misunderstood answer, an old appliance, or a house that isn’t actually owned but “looks like it is”—can end up deciding whether a person can access a right or not.

What Did We Find?

Between 2020 and June 2025, more than 81,000 older adults were excluded from Pensión 65 and later reinstated. Many of them were only able to rejoin the program after a long and complicated appeal process—clear evidence that they should never have been removed in the first place.

The system that determines who receives this pension has blind spots: it struggles to identify cases of abandonment within shared households, penalizes things like electricity use without considering the broader context, and applies outdated criteria that no longer reflect the country’s reality.

Local Targeting Units (ULEs) have serious operational problems: surveyors often lack proper training, receive little supervision, and have limited tools to assess real poverty conditions accurately. But the issues don’t stop there. SISFOH’s Territorial Units, which are supposed to oversee the work at the regional level, have also followed flawed procedures. Peru’s Comptroller General documented cases in which older adults were removed from the system based on unverified reports of death—often relying on rumors or lacking official documents. In each of these cases, the burden fell on the individuals themselves to prove they were still alive.

The appeals process for those excluded is slow, unclear, and often inaccessible—especially for people who are alone, ill, or have no close family support.

What Impact Are We Seeking?

With Invisibles, we didn’t just aim to investigate a technical issue or a public management failure. Our goal was to use journalism to intervene at a critical moment for social policies in Peru. When we began this investigation in December 2024, Law No. 31814 was already in effect—promoting the use of artificial intelligence for economic and social development. And this year, the World Bank approved a $55 million loan to modernize the country’s Social Household Registry—the database that feeds into SISFOH—through digital technologies, data analysis, and even AI-based tools.

In this context, our investigation pursued three main goals:

Expose a structural problem: to show how an automated system that decides who deserves social assistance can end up excluding highly vulnerable people without justification—and why these decisions cannot be left to algorithms that lack quality data and human judgment.

Fill an information gap: we created clear, practical content so that any older adult—or their family—could understand what happened to their pension, how the socioeconomic classification system works, and what steps to take if they were excluded.

Spark a debate on algorithms and rights: this investigation is being transformed into useful knowledge for journalists, researchers, communities, and policymakers. We are sharing it in public forums, workshops, technical roundtables, and training spaces because we believe journalism should not only expose problems—it should help create solutions.

We know that technology can help improve social policy, but only if it’s applied with fairness, reliable data, and an understanding of real-life context. Otherwise, it risks becoming a black-box system that classifies without truly seeing. Our role as journalists is to closely watch how these systems are implemented, explain their implications, and give voice to the people they leave behind.

We thank the IA Accountability Network at the Pulitzer Center for supporting investigations that rigorously examine the use of algorithms in public decision-making—and for promoting journalism that brings evidence to the most important debates in our societies.