After seeing fifty of her sheep die, Amanda Alegría is resigned. She knows the river where her animals quench their thirst. The river with the color of the sunset carries death with it. Death is in the reddish water coming down the river Aymaraes, staining the stones on the banks with the color shade of bricks. Amanda says this has been happening for two years, but maybe it has been longer. She speaks fluently even though the cold bites her like a mad dog in these extensive treeless plains, a dog she is not afraid of because she has been living in the punas[1] for fifty-something years. She looks after livestock - seven hundred heads of cattle - dispersed around the highlands full of ichu[2] and dry grass. The livestock is not hers; life is not that fair. She works for the Chulla community in the Huancavelica region; every day, she grazes the cattle and takes them out to drink water; in the afternoon, she takes them back to the farmyard.

—What time is it now?

—Three o'clock

—At around one or two, the wind brings the dust and makes you cough hard.

The wind, a word that will appear several times in this story, always linked to a cough, a complaint.

All one can see around is dry grass. A solitary wasteland covered with dust. Where does the dust come from? The town of Atcas is just a few kilometers away, in the Yauyos province, in Lima, where a small group of families lives. It is a place anchored in the mountain range with hills full of gold, or rather, once were. Since 2008, the Peruvian mining company IRL S.A., founded in 2002 by Jesús Armando Lema Hanke and Eduardo Gracía-Godos Meneses, has extracted the metal with permission granted by each resident. It is an open pit mining operation that has already swallowed several mountains. We will be there in a few hours. In the meantime, Amanda Alegria says she hears explosions at noon; after that, the wind brings a cloud of dust that irritates her throat constantly. However, she has already gotten used to it, like the cold. She wears a black hat, a thin brown sweater, and a blanket to cover her back. It seems Amanda has made a below-zero pact with the weather. She does not feel the cold. The photographer and I have wrapped up to our noses. Despite her resignation, Amanda does not get used to seeing her animals die. It is normal during the frosts, not during the rainy months of January and March, or when they drink water from the river.

Her complaint is not the only one. Arístides Gómez lives further up with his wife Rosa Huamanlazo on a dusty road that cuts through the bleak landscape of the central Andean region.

The couple's refuge is a straw hut surrounded by a circular stonewall. From there, walking downstream, lie their two-hundred camelids: llamas and alpacas that stretch their long and wooly necks when sensing our presence. They say that yesterday one died – another one of the more than a dozen they have lost in the last two years. We walked through the mud, sinking our shoes in the puddles. The little black and white critter is on the bank of the stream. It is wet like a dirty cloth, inert. It has a swollen belly; its eyes are half-open as if still suffering. It died yesterday, Rosa Huamanlazo said, crying uncontrollably.

—One complains to the company just for the sake of it; they do not listen —Arístides tells me in the car.

—I once cut open an alpaca after it died. It had a swollen heart; the liver was white. That is how these animals die — says Rosa, a shepherd living in a wasteland called Shutocmachay.

The stream these animals get water from is also called Shutoc. It is a small creek that rises in the upper lakes, close to the mine. It flows downstream to join the Chacote River, a tributary that carries little water in June and November. While Arístides Gómez tries to explain his legal battle with the mining company, I bend down to pick up a stone; the color has called my attention. Is it natural? The water is murky and suspicious. I barely touch it; still, it stains my hand, trying to tell me something. Pollution? I pick up another stone a bit further on, away from the bank, and this one is different, of a reddish color, but it does not convey danger.

—And further up—Arístides tells us—is worse. The contamination has burnt the pastures. Animals do not go there anymore.

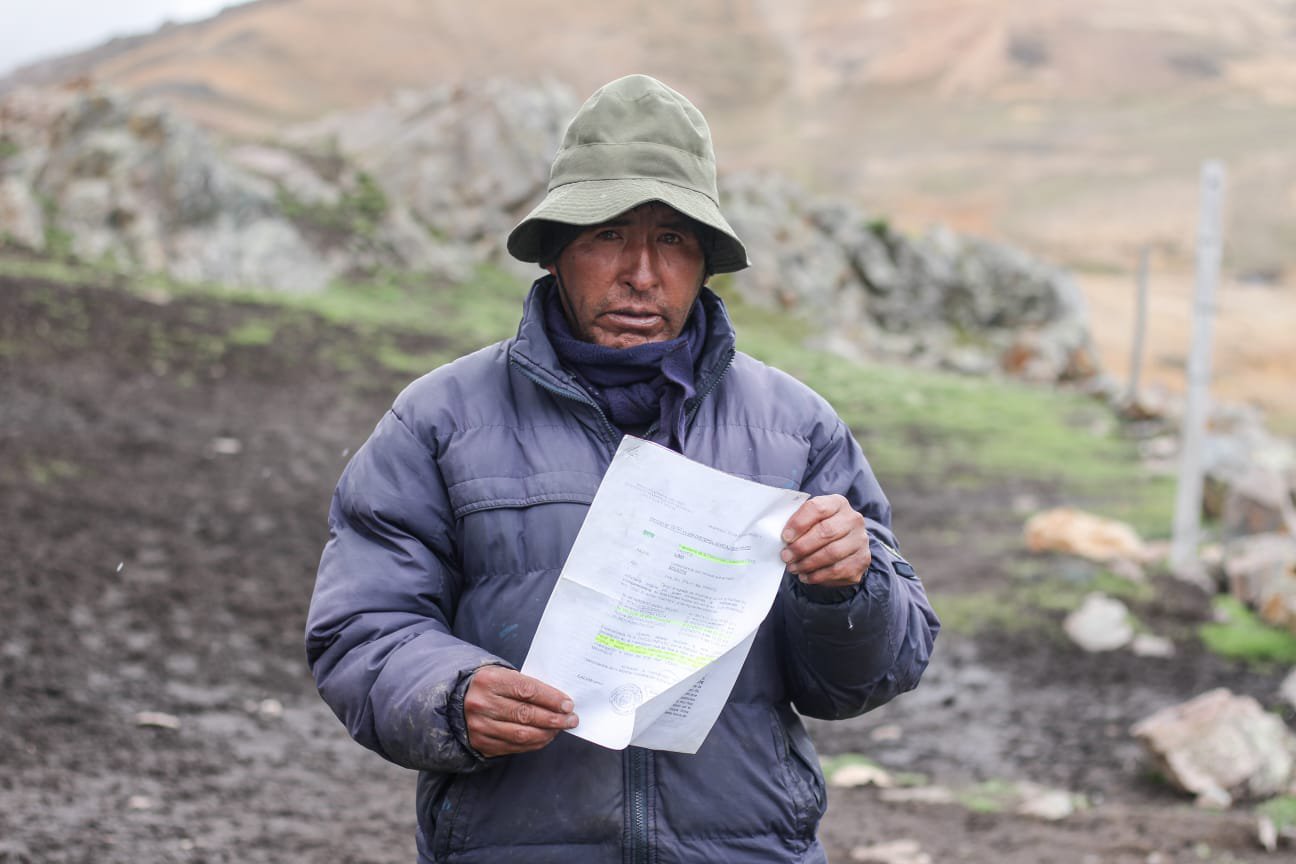

Gómez, a short man with rough hands and a thick voice, denounced Minera IRL S.A. to the Agency for Environmental Assessment and Enforcement (OEFA in Spanish) in 2019 and 2020. He accused the company of polluting the pastures, poisoning the water, and invading his land, but that is another matter. As we ride in the van, accompanied by a clickety-clack noise, Gómez shows me copies of his complaint documents. It includes the summons made to his wife, a notarized letter he sent to the company, and another letter that the Atcas community sent him demanding not to mess with the mine because they argued he's not even a communal landholder. He stretches out the papers as a sign of his dignity intact. His voice does not tremble. Instead, he accuses Atcas of keeping quiet about the pollution and the mine of not compensating for the damage. Arístides, the pastures' advocate.

The van stops, or rather, he orders the driver to stop.

—If we get any closer, we will get into trouble with the guards in the sentry posts —better do it from here, look over there —he points to a black plain of brown craters.

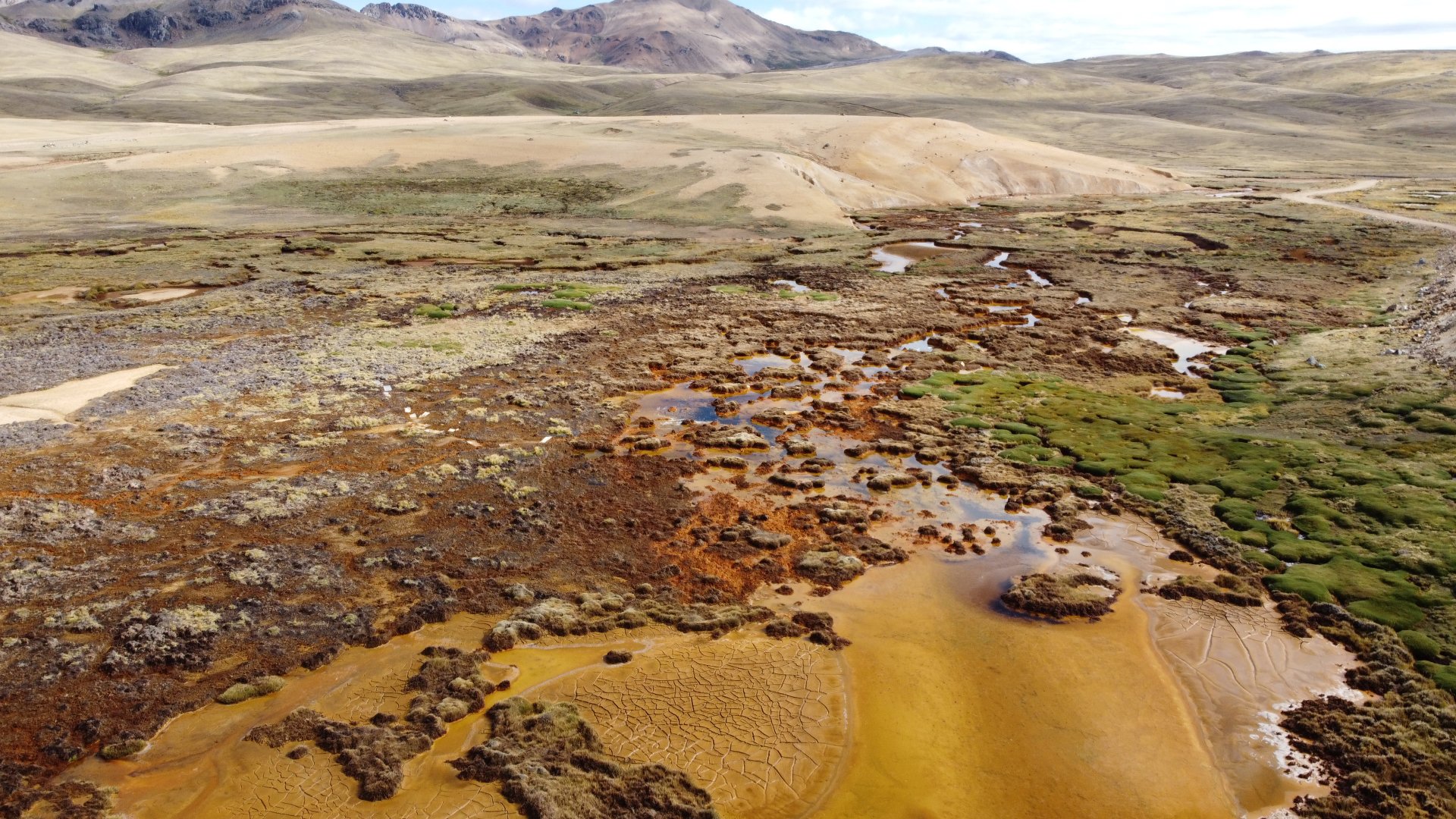

We walked a long way to see well. Arístides has put on a mountain pass that only leaves his eyes uncovered. The place is desolate, silent as in a cemetery. The pastures move slowly, and the water flows without making any noise. Who would worry about a polluted stream in the highest puna of a valley five thousand meters above sea level? Who would be affected if not a soul passes through here? When Repsol spilled 11,900 barrels into the Peruvian sea in February 2022, there was a global scandal. In 2020, Minera IRL S.A. spilled 27 cubic meters (27 thousand liters) of acid water into the Chacote and Aymaraes rivers, and its discussion in the media was sad and shameful. At the time, the National Water Authority (ANA) found aluminum, arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, copper, iron, manganese, nickel, and zinc in the water around an area covering 45 kilometers, just under half of what Repsol had polluted on the coast of Lima (80 km, according to a U.N. report). But the media did not come here to photograph dead parihuanas, the more than a meter-high flamingo that is said to have inspired the design of the Peruvian flag. Arístides says that sometimes they appear dead on the banks of the lakes and the shepherds' dogs pluck them. Usually, birds are the best indicator that something is wrong with the environment. They adapt faster than humans do by 135 years. Even so, it is hard for them to adjust to the accelerating environmental changes the planet is experiencing. In 2020, the mining company was sanctioned with a penalty of 150 tax units (ITU in Spanish), an average of S/ 645 thousand ($167,380 USD). The Minera IRL appealed the decision arguing that the dumping occurred due to heavy rain and not to any oversight on their part.

We have reached the edge of a marsh. We are very close to one of the mine's sentry posts. The name of this plateau is Pampa Sillani. Looking very intently, one can see how the green of the grass takes on a dark color. The muddy water devours the small islands of pasture, turning them into tiny black mounds. Nature disappears to give way to drainage, dirty liquids, poisoned water, and a red creek. There they draw undulating shapes as if someone had emptied death-colored oil everywhere. The wetland where Aristides and other shepherds grazed their cattle is dead. We have to rush away now. We live behind a land torn apart by the pollution the mining company repeatedly denies causing.

The small streams that cut through this place flow into the Chacote River, discharging its misery into the Aymaraes. It then reaches La Virgen, a larger tributary that joins the Canipaco River downstream. Finally, the Canipaco, whose waters benefit all the communities around, flows into the Vilca River, which, in turn, gets to the Mantaro. This long river, which takes its name from the Mantaro Valley in central Peru, irrigates the lettuces and potatoes that go to the markets. Looking at it this way, the pollution that happens at five thousand meters above sea level does not seem so isolated. It is like an echo that repeats itself silently.

—Those animals are not good anymore; they are contaminated—the van's driver tells me when I notice some camelids drinking in the Chacote River. Their meat is up for sale.

These camelids are sought after not so much for their meat, but for their wool. According to the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Irrigation (MIDAGRI in Spanish), in 2020, Peru was the world's first supplier of alpaca wool, with China, Italy, and South Korea as the main markets for the precious wool that covers the body of these long-necked animals. Data published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) shows that 70 to 80 percent of the family income in these areas depends on selling Alpaca wool. That is why people shed tears of pain over the death of a baby alpaca.

“Bitter lands/homelands of ash” says a verse in a poem by Manuel Scorza, a piece of poetry that falls like an autumn leaf in this bleak landscape. The pain here started a few years ago. According to Andina, the Peruvian news agency, the complaints regarding pollution caused by mining operations began in 2008. "More than two thousand people living in Huancayo and the department of Huancavelica took to the streets in Huancayo to protest against the alleged pollution caused by the mining company IRL," Andina reported. That same year, IRL had started its operations in the Corihuarmi mine, which in Quechua means “golden woman.” Was that protest a symptom of what was to come or the exaggerated reaction from people rejecting development through mining? The reports and sanctions that the Environmental Assessment and Monitoring Agency (OEFA) would issue against Corihuarmi in the following years and to which Salud con Lupa gained access revealed signs of a recurring behavior: non-compliance with the regulations to protect the environment.

After having walked through the burnt pastures, we said goodbye to Arístides. He heads off to the hut where his wife awaits him. Then, we continued our journey to Atcas, the community that permitted the mining company to exploit their land.

—Aren't you afraid of reprisals against you?

—I am used to it. A few months ago, they sent some drones flying over my hut. When I complained to the company, the police hit me and sent me away. These people are bullies.

I called him a few weeks after the incident; this time, he told me he was scared. The company sent drones again, and he decided it was best to leave. He is now in Huancayo, the capital of the Junin region, four hours away from home. A shepherd will look after his animals. He is not panicking. His voice is full of anger, with a thirst for revenge. He also told me the police had summoned him to testify concerning an investigation opened by the Ministry of the Environment against the mining company. "I'm sure it has to do with our protests and what the newspapers published," he says. In addition, the Prosecutor's Office will inspect the mine in July. Arístides' voice sounds worn down by the many blows he has endured and all the waiting as if his resistance is now a mere administrative and police formality.

Before 2016, the Agency for Environmental Control and Contamination or Pollution (OEFA in Spanish) issued eleven sanctions against the Corihuarmi mine. The fines added S/ 2 320 941 ($597,740 USD). The reports documenting these violations show a recurring pattern: "Non-compliance with the Maximum Permissible Limits concerning the potential parameter of hydrogen (pH)," read in resolutions N° 217-2013; 269-2013; 014-2014 and 002-2016. The quote reads like a chemistry lesson, but in non-technical language, what it means is turning the water into an acid liquid, not suitable for consumption and highly detrimental to the development of any kind of species. This is due to the handling of heavy metals the mine uses, according to what María Aguilar, an environmental engineer with experience in mining issues, explains. There is also non-compliance regarding the construction of what is known as coronation canals, a kind of ditch where rainwater flows and where the tailings would run if any pipes were to break. These cases appear in resolutions N° 263-2012, 033-2013, and 117-2013. Minera IRL has appealed some of the sanctions related to these channels.

What stands out is that IRL agreed to pay only certain fines and brought those related to inadequate infrastructure to court. The seven resolutions to addressed by the Commission included breaches such as:

- Storing cyanide in inappropriate places.

- Pouring the effluent from the sedimentation pond effluent into the environment without complying with the maximum permissible limits.

- Leaving the work of controlling infiltration and water runoff unfinished.

- Initiating open-air extraction activities without the authorization of the Ministry of Energy and Mines.

- Not building a retaining wall for the removed soil dump or placing the Geogrid cover on the slopes.

The language of those reports is harsh, but it shows that Minera IRL is not, or was not, doing things according to the norm.

The mining company denies having polluted the area. Magaly Villena, manager of Social Responsibility at IRL, points out that all the above violations are mere findings. "In the ongoing supervision process OEFA does as part of the audits it carries out in the country's mining companies; it identifies which findings need to be formalized. OEFA has not had observations or findings about the company since 2016. It has also determined that our company has not had any recurrences," Villena told us in an email. In the same message, she stressed, "the company has never been fined for environmental damages or pollution." However, the resolutions issued by OEFA and the deterioration of pastures and animals tell a different story.

I insist with Villena on this point, and she replies that the findings reported by OEFA refer to "observations about the construction or benchmarks of certain infrastructure in areas not in use, and not to damages or any environmental harm." However, the fact is that deficiencies in the infrastructure caused the dumping of toxic waters. For example, according to Resolution N° 014-2014-OEFA/TFA-SEP1, the effluent from the outflow of the dump exceeded the maximum permissible limit. What do we call this, then?

How long can nature bear this situation? What about closing the mine? Arístides asks these questions while he shows me the documents he brought with him in his backpack. It is a valid and understandable question. He wants to know if there is light at the end of the tunnel or if all he has been fighting for is in vain. As an environmental lawyer specializing in environmental law, César Ipenza has the answer to some of Arístides ‘questions. “In our legal framework, it is impossible to cancel an operation of this kind for non-compliance with environmental obligations. However, from an OEFA standpoint, it is possible to suspend operations as long as there is evidence of pollution or breaches of the law. One recent suspension of discharging operations happened earlier this year following an oil spill in the Pampilla refinery, which belongs to the Spanish firm Repsol."

A town living in fear

It has been an hour since we left Arístides Gómez, and we are about to enter the community of Atcas, in Lima. The mining operation occurs very close to the intersection between the Junín, Huancavelica, and Lima regions. As it happens, one moment you could be in Junín, and the next in Lima, just as we are now. From the hills, one can see four columns of calamine roofs aligned like a martial battalion, with a narrow and rocky river flowing through a ravine. The community there granted permission to the Minera IRL S.A. to exploit 3 300 hectares of its land, sixteen times the area of the principality of Monaco but without its wealth. The area where this peasant community settled covers twenty-seven thousand three hundred and ninety-nine hectares. However, the village of Atcas is a small settlement of adobe houses. Others are brick and cement buildings such as the school, the stadium, and the municipal hall. All homes have electricity, Direct T.V., and mobile phone signal, but no connection to the Internet. Atcas is a small town with dirt streets that sits at the foot of a mountain watching over us like Polyphemus, one of the most famous Cyclopes in Greek mythology. Some people walk towards the square. They do not stop; they move fast, like the wind blowing hard. The community has gathered in the square, a set of well-kept concrete sidewalks and shrubs, to discuss the problems affecting the community. People look at us and see a couple of strangers visiting a town at the end of the world.

There is silence in the streets of Atcas. A little llama passes by; she is distracted and recently escaped from a farmyard. Everyone has to attend the assembly; even those who live outside town, in cities like Huancayo or Huancavelica, have arrived to attend the meeting. They have come in vehicles that are now parked outside the main square. In the medical center, a sign written on a sheet of bond paper with a down with almost no ink reads: “In case of emergency, call 9718963...”; above, in bright acrylic colors, the mining company also has a message to convey: “Permanent information office CC.CC. Atcas. Opening hours....” The differences jump up to the walls. A few steps away, a woman peels a ram in front of her house. She does it alone, using her right hand as if the knife was an extension of her fingers. She looks at us with suspicion; she knows nothing about contamination. She points her finger in the direction of the square. "Ah, over there, ask the president," she says. We see some adobe houses falling to pieces, gone are the days when they sheltered entire families. The Pentecostal Evangelical Church of Jesus Christ displays its sign with the days and times of its worship services. Today is Friday, and the church is closed. All the people have gone to the square to hear complaints and present theirs. Some clothes are drying on a stone on the riverbank, where the village ends. We have walked the streets and seen the walls full of graffiti. We toured around the stadium with its basketball board, the laundry place, the closed shops, the garden with its rusted and twisted swings, and the half-built school. The town receives about 200 thousand dollars a year from the mining company, and one wonders whether gold mining is really helping people here or only offers them an illusion.

The mining company says that since 2004 it has paid $1,268,200 USD to communal landholders for the use of their land. It also says that it has promoted the creation of collective enterprises that nowadays provide services such as laundry and transport for IRL personnel. However, when I ask them, the landholders fail to mention the benefits they get in exchange for their permission to exploit the mine. The company is proud of its social programs, including cattle breeding, the building of a health center, and the maintenance of passable trails. Nevertheless, despite all this, Atcas looks poor.

A man approaches us and asks who we are and why we are here. He checks with the assembly, taking his time. Meanwhile, we wait at a distance; people turn to see us. We hear someone asking, "Who invited the press?” Finally, the man comes back. He kindly told us that soon we would be able to join the meeting. The hills surrounding this community are full of gold, a metal linked to luxury and elegance; palaces and weddings; pharaohs and conquests. In Atcas, the closest to gold the communal landholders have ever seen is the sun shining but without burning. The rest are old doors, the tin of the calamine, and rusty irons. The men and women at the meeting, all wrapped up with blankets and wooly hats, do not know that in 2021 the gold extracted from their hills went to Switzerland, the country IRL exported 910.75 kilograms of gold, nearly a ton, for a total amount of $44,394,770,90 USD. It is easy to imagine vaults full of gold bars like those seen in Hollywood movies. However, the World Gold Council estimates that all the gold extracted since 1950 would merely fit a bucket of 22 meters on each side.

Moreover, if instead of gathering it in one single place, we were to share it, it would be an unequal distribution. Most of the gold on our planet can be found in jewels and first-world countries or nations with ostentatious traditions. In India, 50 percent of the annual demand for gold comes from wedding ring manufacturers; a vanity custom also shared by the Chinese. Gold is also present in everyday objects: the red lines in a pregnancy test kit are activated by gold nanoparticles, and those tiny connectors on the integrated circuits of mobile phones are all made of gold. The James Webb telescope has captured the sharpest images of deep space and has an inbuilt six-meter long gold-plated mirror. Gold seems to be everywhere.

The man who had asked us to wait outside is now inviting us to get closer. While in the distance, we heard some complaints against Corihuarmi about the dead animals, how tedious it would be to take the mining company to court, plans to stage a protest next year, and more. Now, it is our turn to address the assembly. I stand beside Edwin Rodríguez, the community's president, and explain my presence before the curious and tired look of mothers carrying their children, men with severe faces in puffer jackets, and the elderly members of the community. "Why have you come here?" I sense they do not want a speech full of hot air. So, I go straight to the point and ask: Does the mine contaminate your land? Is it affecting you? What follows is a resounding silence. It does not last. People exchanged glances, one urging the other to speak out. Rodriguez looks at them all; his leadership is on the line.

“Gentlemen,” he dares, “that is the question. At the time, we wanted to do something, but...” he doubts, words are stuck. He has spoken first and now asks his people to express themselves, but his people choose him to answer for them. Not an easy task, though, because to admit there is pollution is to come across as passive victims: “We wanted to do something, but... suddenly... collide with... many have called it the monster.”

The monster. There is no doubt what he is referring to. The giant that eats up their ancestral hills and preys on their environment. "Yes, it is polluting. Which mining company works in a responsible way? I think none does; pollution always happens. Here, we have people who are affected by it. There's this lady here" – he points to a woman looking down –"and there's Mister Olimpo here; they both live close to the mining operation; what else could I tell you."

Rodriguez has managed to ease the tension among those attending the assembly. Instead, they turn to others and make comments among them.

«The most badly affected are those living downstream. We can say that Minera IRL is polluting these areas; all mines contaminate," Rodriguez insists, as if fear has given way to a renewed impulse to denounce. “The Chacote River is contaminated; OEFA says it isn't. However, we have proof of that, fines against the mine. With those five fines, OEFA could have closed the mine, but they don't do it,” he says in a loud voice, annoyed.

Just as in Atcas, many communities are fighting against the mining industry. The Nuevo Renacer (New Rebirth) Committee is an organized group in the Dominican Republic that fights against the contamination of Pueblo Viejo; until 2019, the second largest open pit mine, managed by Barrick Gold, a Canadian multinational that operates the primary gold mines in the world. Located in the Sánchez Ramírez province, the mining operation in Pueblo Viejo affects approximately 600 families. Nuevo Renacer is no longer asking for the closure of the mine, but rather for the relocation of the communities. The people of Atcas, on the other hand, could not leave their wasteland; this is all they have. Besides, they have not asked for relocation. Environmental lawyer Ipenza favors some sort of compensation: "From a legal point of view, there could be a process of compensation and severance pay in the case of damages to people's health or their properties," he says.

Someone in the assembly raises a hand to ask for the floor. Watching their leader speak up has encouraged others to do the same. We take the camera out to record the moment; whistles and complaints from the crowd refrain us from doing so. No cameras allowed, says the president. The man is tall, with short hair and a fair complexion. He knows about the work in the mines and wants to support his leader. "The community depends on livestock, we have no agriculture, and we have no other sources of income. Pollution not only happens downstream. The blasts occur from noon to quarter past one. They use an ANFO compound made from ammonium nitrate and highly polluting fuel oil. They control the movement and the scattering of the rock, but the wind spreads considerable amounts of dust 500 to 800 meters away, sometimes more.

I recall Amanda Alegria's cough, the shepherd we mention at the beginning of this story. I now understand why she could not stop coughing despite being so far from the mine. I now know what it means to cough incessantly in a treeless plain - a pampa - like this one, where the air should be clean.

When answering our questions by email, IRL's Magaly Villena insists that the blasts do not affect the population. "It takes place daily, in specific areas and once a day, complying with management and safety regulations and the relevant permits. Villena adds that the communities know of these procedures ahead of time. She is adamant that neither noise nor dust can reach the community of Atcas, which is 40 kilometers from the mine. However, she has not heard Amanda cough every afternoon or the testimonies coming out of the Atcas assembly.

“Does the company do something to assist you with your health?,” I ask the man taking his turn to speak to the assembly.

"No, nothing," he says while others back him up. "Nothing; they have made many unfulfilled promises. We have protested and talked to the shareholders and the board of directors, but nothing has been done. All they do is produce the records of the meeting", the man says. His fellow landholders look around to see who will clap first, but the complaint at hand is too severe to celebrate.

In Tanzania, the North Mara mine was fined €2.2 million in 2019 for leaking toxic waste into groundwater, underground rivers, and streams. North Mara, whose majority shareholder is also Barrick, is a gold supplier for giants like Nokia, Apple, and Canon, companies that should buy conflict-free gold. According to Resolution N° 033-2013-OEFA/TFA, in 2009, the Corihuarmi mine discharged waste from a sedimentation pool into the environment. Since then, it has refused to pay the fine and instead has taken the case to the Judiciary.

Another landholder, the eldest in the community, has taken the floor: "I have been affected. I would take you there to see how the pasture, it is not as it was. I have seen my sheep die, and all the others are doomed animals. Why? Because of the dust that pollutes the pasture and the water," the man says with anger, his voice and body trembling. Nevertheless, he is grateful I have made it to his community and asks me to voice his concerns to the world.

One more man will ask for the floor; the assembly is no longer fearful but confident and brave. They ask me to help them by providing all the evidence I have so they can take action.

"We have had several meetings in Lima, not just one, but several. They talk to us in their jargon, using words we do not understand, but what we know is that our animals are dying. The trouts are still alive in the lagoons but are sick, and we are eating them. That's how bad the situation is," the man says.

The death of these animals seems to contradict the mining company's argument. Their spokesperson says that environmental care is their priority, which is why they carry out four monitoring activities every year with delegates from the communities in their area of influence. In addition, the company carries out six other environmental monitoring events each year in compliance with the study on environmental impact. She hopes her arguments will help prove that no environmental damage has been caused in the area. However, she falls short of providing the results of those studies, saying that they have been handed over to the OEFA, the Ministry of Energy and Mines, and the communities. Why, then, does the assembly complain? If the company is doing its job correctly, where do these claims come from then?

The doubts I had before arriving in Atcas have all been dispelled. A community has just shouted the abuse they have been subjected to. A private confession they asked not to be recorded. I did it anyway. Why are they so afraid? If they wanted, they could refuse to grant permission to the company to exploit their land and start recovering it for themselves. Nevertheless, they need the money. If their animals die, at least they have that other safe income. If the community was to hire a lawyer who knew about environmental law, perhaps they could better assert their rights and fight more for their natural environment.

César Ipenza insists on the possibilities offered by environmental law. Although the mine has paid for its sanctions, it is not the logic of a responsible operation: polluting and then paying the fines. Instead, companies must avoid damaging any form of natural life at all costs. "The legal framework indicates that companies must prevent, mitigate or monitor the possible impact their activities could generate. And the job of OEFA is not only to sanction and impose fines for non-compliance with the rules but also to prevent environmental damage," says the specialist.

After the meeting, the same man who approached us at the beginning came after us to tell us that those in the community wanted to buy us a plate of food. They are grateful we have come; no media outlet has ever been here. The dining place is on a corner of the square. We settle at the long table covered with a plastic tablecloth, and the woman serving is surprised by our presence. After bringing the main dish, she sits on a stonework bench and stares at us. Have you come to see what pollutes the mine? she asks, sparing her words. Her testimony will be the last we hear on this trip: she talks about the lack of attention, more deaths, and fewer medicines. She also mentions one more argument so we can understand why the people of Atcas do not complain. «Huantán is very supportive of the company. If Huantán would stop working as we have done before…" she does not finish her sentence. "But, of course, it is clear that Huantán is not affected; we are the ones suffering the consequences." Huantán is the district the community of Atcas belongs to; the capital is two hours away from here. Although the land also belongs to Huantán, the distance that separates it from the mine protects its people.

The journey back reminds us that the voices we heard in Atcas are striking and authentic. The outlook is bleak. Some llamas cross the road running; I wonder if they are afraid of the noise from our vehicle or fleeing away from their fate. "They're going to die this season anyway, either because there is no water or it is already contaminated. What can one do? It's the sad reality," Arístides tells me. The mining company has promised to stay in the area until its operating license expires in 2024. Maybe the environment here cannot wait that long.

Translated by: Mariusa Reyes. / Edited by: Julia Knoerr

This report is part of Historias Saludables, a training and support program for producing news stories about health and the environment, led by Salud con Lupa with the support of Internews.

[1] Puna. A plateau in the Andean region. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Puna

[2] Ichu. Commonly known as Peruvian feathergrass, Ichu is a grass species in the family of Poaceae native to the Americas. https://spain.inaturalist.org/taxa/333048-Stipa-ichu