The stolen birth: The most painful side of giving birth in Latin America

At the beginning of the last century, giving birth to a child was no longer an intimate and instinctive experience. Houses were changed for delivery rooms, they sped up women’s contractions with synthetic hormones, maneuvers and cuts were made to women to deliver the baby faster. Although these techniques appeared to protect women and children’s well-being, unjustifiable medical intervention became more and more into a global epidemic. Today we live immersed in a culture which silences mother’s instinct with medical instructions.

However, birth modernization left apart an essential principle: women’s bodies are designed to give birth as long as it can follow its physiological time and be done in secure and familiar conditions. Births can not be standardized because they are unique and unrepeatable. Besides a woman lying on a gurney about to give birth can not lose her will. As it is related to her body, protocols and medical assistance should be approved by her. But it never happens.

For many years, millions of women have given birth in hospitals and clinics without any questioning. They assumed it was normal that some metal forceps held her baby’s head to deliver it faster, that they were injected with synthetic oxytocin in order to make the birth faster or that they were brusquely pushed in their bellies for making an inducing labor. They were also exposed to a method that became popular in vaginal births and which consists of cutting the perineum to make the way out space of the baby bigger. This surgery is called episiotomy and many times it is done without the woman’s consent. In other cases, caesarean sections are scheduled but there are not any serious risks that justify them. They are made just for one reason: it is more expensive and faster than a natural birth.

Every second, 5 or 6 babies are born. Every year, 135 million women give birth.

But in the last three decades, significant scientific research has shown that these medical procedures are riskier and not beneficial for women and the newborn baby. In fact, the horizontal position is not the most efficient one to give birth. It was demonstrated that the ancestral squatting or vertical position let women make less effort, feel less pain, reduce bleeding and the chance of suffering from a tear. Science has also shown that between 2 and 8 out of 100 women could have some difficulties at a natural vaginal birth.

Despite the current available knowledge and the crucial struggle of the feminist movement in order to make the medical community restore their practices, there is a great resistance to do so, as many health professionals did not want to see the violence they were used to. As it happened to feminicides and hate crimes, this kind of aggression towards women had to be named with specific terms so we can start to recognize it: obstetric violence. Now women can define what they went through in gynecological offices, operation and delivery rooms. Many years had to go by until the World Health Organization and different governments start to understand obstetric violence as it is: a public health problem.

"To change the world, first you have to change the way you are born."

Michel Odent

Since 2014, the WHO has discouraged risky procedures in birth assistance and it promotes “a decent treatment to women’s body and the respect of her will and physiological time to give birth.” Birth is no longer considered as a medical act or as a disease which is treated with harsh standards. Birth is an experience that every woman goes through in a unique way. The only essential requirement is that the mother is well informed, comfortable and that she feels accompanied when making decisions: about the most comfortable posture for her to give birth but also about the right to hold the baby in her arms during the first minutes.

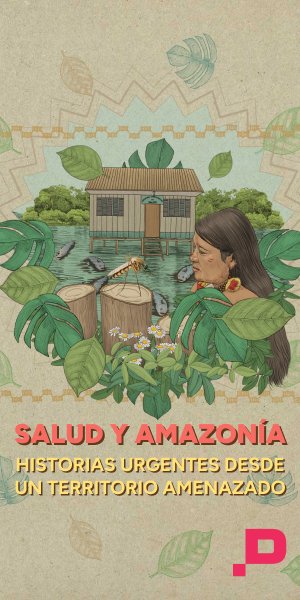

Therefore, Salud con lupa presents “The stolen birth: the most painful side of giving birth in Latin America,” which is a research based on the testimonies of 27 Latin-American women of different ages who were mistreated and subjected to non-consensual risky medical practices at births.

During six months, journalists from Argentina, Ecuador, Chile, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela spoke with them, found out about the way these births are assisted in these countries, which are the clinical practices that are imposed, the kind of available data for pregnant women and which are the conditions that make them more vulnerable towards the obstetric violence. We also interviewed public health researchers, obstetricians, midwives, feminist movements, lawyers and government officials who are responsible for guaranteeing sexual and reproductive health to people. In all the countries, hospitals and clinics where the facts recounted by these 27 women took place do not recognize their practices as obstetric violence and as a crime. Besides they do not inform pregnant women about their rights regarding the birth assistance.

In a world where having access to reliable information is a privilege, “The stolen birth” is a way of contributing as journalists to make it possible for women to be informed, to recognize in other mother’s testimonies that their children’s birth can not be treated as a business and that it does not imply an outrage upon dignity with practices that can damage them. “In order to change the world, we must first change the way we are born,” says Michel Odent, a French physician since the beginning of the ‘80s. We still have the chance to make that pending revolution real.